Shell knew about the relationship between burning fossil fuels and climate change as early as the 1980s. So what did the company decide to do about it? Stop burning fossil fuels?

No. It changed its advertising strategy.

A tranche of documents uncovered last week by Jelmer Mommers of De Correspondent published on Climate Files, a project of the Climate Investigations Center, revealed that Shell knew about the danger its products posed to the climate decades ago. The company has continued to double-down on fossil fuel investment since the turn of the century despite this knowledge.

But in the wake of a bribery scandal in Nigeria that resulted in two dozen employees being fired, the company was concerned enough about its dirty image to work out a new PR strategy.

That strategy was presented in a document from 1999 entitled ‘Listening and Responding: The Profits and Principles Advertising Campaign’. The dossier shows the origins of Shell’s PR strategy to clean up its image, enacted over the past two decades.

And what does it show? “Greenwashing”, Savannah Law School associate professor Judd Sneirson told DeSmog UK — Shell is “misleading consumers about its environmental practices”.

And it’s easy to find examples of the strategy being deployed right through to today.

Climate Concern

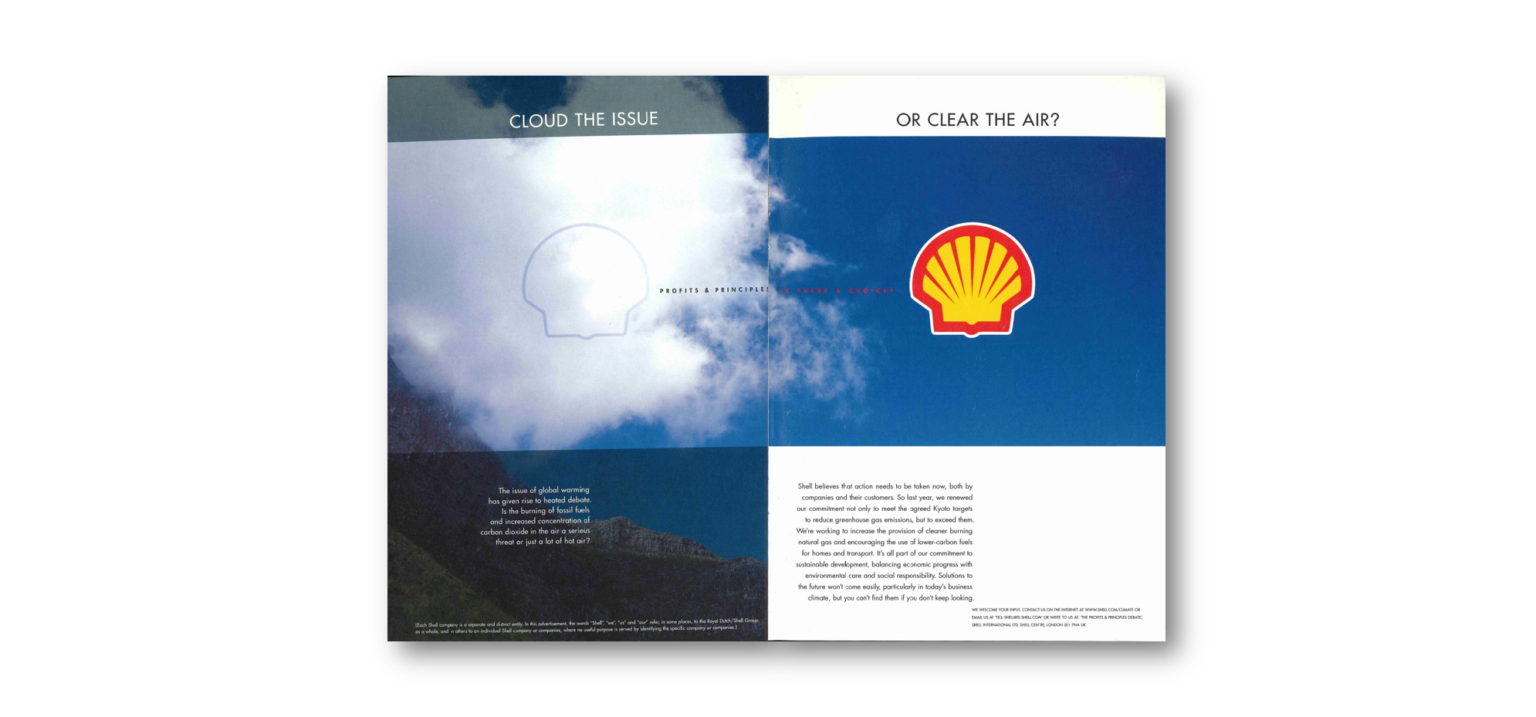

In the document, Shell presents “the first pool of examples” of adverts that allow the company “the opportunity to extend our point of view in a frank and open way”. The document includes a series of adverts — some real, some hypothetical — in a ‘don’t do this; do this’ format.

This slideshow put together by DeSmog UK shows the negative and positive adverts side-by-side:

One of the first adverts in the dossier concerns climate change. The document recommended the company tackles the issue head-on; Shell should “clear the air”, not “cloud the issue”.

The hypothetical bad advert reads: “Is the burning of fossil fuels and increased carbon dioxide in the air a serious threat or just a load of hot air?” This is not what Shell should advertise, the document suggested.

Instead, the document recommended Shell promotes its ‘green’ activities such as its commitment to the Kyoto Protocol, natural gas production and sustainable development.

Jess Worth, co-director of campaign group Culture Unstained, said such efforts show how seriously the company was taking its image reboot going into the 21st century.

“To understand what Shell is trying to achieve here and why, you need to look at what was going on at the time,” she said.

She pointed to the damage to Shell’s reputation following the controversy over the disposal of the Brent Spar platform in the North Sea, and accusations of responsibility for the deaths of tribal leaders and activists in Nigeria.

“Concern about climate change was also starting to enter the mainstream, and the Kyoto Protocol had just been signed, with much fanfare”, she said.

“So what did Shell do: shift its business model away from primarily investing in ever-more polluting fossil fuel projects, enshrine the right to free prior and informed consent for local communities, clean up the mess it had made in Ogoniland and fully commit to developing genuinely sustainable alternative sources of fuel? Nope. Shell did the opposite, in fact.”

“It launched this marketing campaign, in the knowledge that if it could just rehabilitate its reputation, business as usual on the ground could largely continue,” Worth added.

“… bury the findings, muddy the waters, and turn climate change into a ‘debate’.”

To this day, Shell’s ‘solution’ to climate change continues to be to invest in fossil fuels, albeit sources with marginally lower carbon footprints such as natural gas, which is claimed to produce about half the CO2 emissions of coal when used in power generation.

Shell’s new “Sky” scenario, which outlines how the company thinks the world can prevent warming of more than two degrees and was released in March 2018, relied heavily on as yet unproven carbon capture and storage technology.

That would allow companies like Shell to keep producing and selling fossil fuels for much longer than if policymakers enacted more radical but effective strategies such as massively increasing the share of renewable energy.

Campaigners in the Netherlands recently announced they would take the company to court unless it could prove its business model was in-line with the Paris Agreement’s two degrees goal.

In response to DeSmog UK‘s questions about whether the company accepted the characterisation of its strategy as greenwash, a spokesperson for Shell pointed to its sutainability reports and a quote made by the company’s CEO Ben van Buerden at the time the document was published:

“Tackling climate change is a cross-generational, global and multi-faceted effort,” van Beurden said.

“This is a challenge for the whole planet, for all of society, for customers, for governments and indeed for businesses. It will mean meeting increasing energy demand with an ever-lower carbon footprint. And it is critical that our ambition covers the full energy lifecycle from production to consumption. We are committed to play our part.’’

But despite Shell’s supposed commitment to climate action, it plans to keep 95 percent of its investments in fossil fuels, putting just five percent into renewables. And latest data shows that Shell’s emissions have risen to their highest level since 2014.

That business model explains why Shell has sought to put a sticking-plaster over the issue of climate change rather than invest in alternatives that could realistically address the issue, law professor Sneirson told DeSmog UK.

“It should come as no surprise that Shell (and apparently Exxon and the rest) have known about climate change for decades,” he said.

According to Sneirson, the #ShellKnew revelations suggest that, within the industry, “climate change ‘denial’ is not a genuinely held position; ‘deniers’ dispute the science in service of the coal and oil industries, lying for profit while literally destroying the planet.”

Instead, Shell’s strategy as presented in these documents is “bury the findings, muddy the waters, and turn climate change into a ‘debate’”, he said.

Shell is yet to directly respond to the #ShellKnew revelations.

Social Conscience

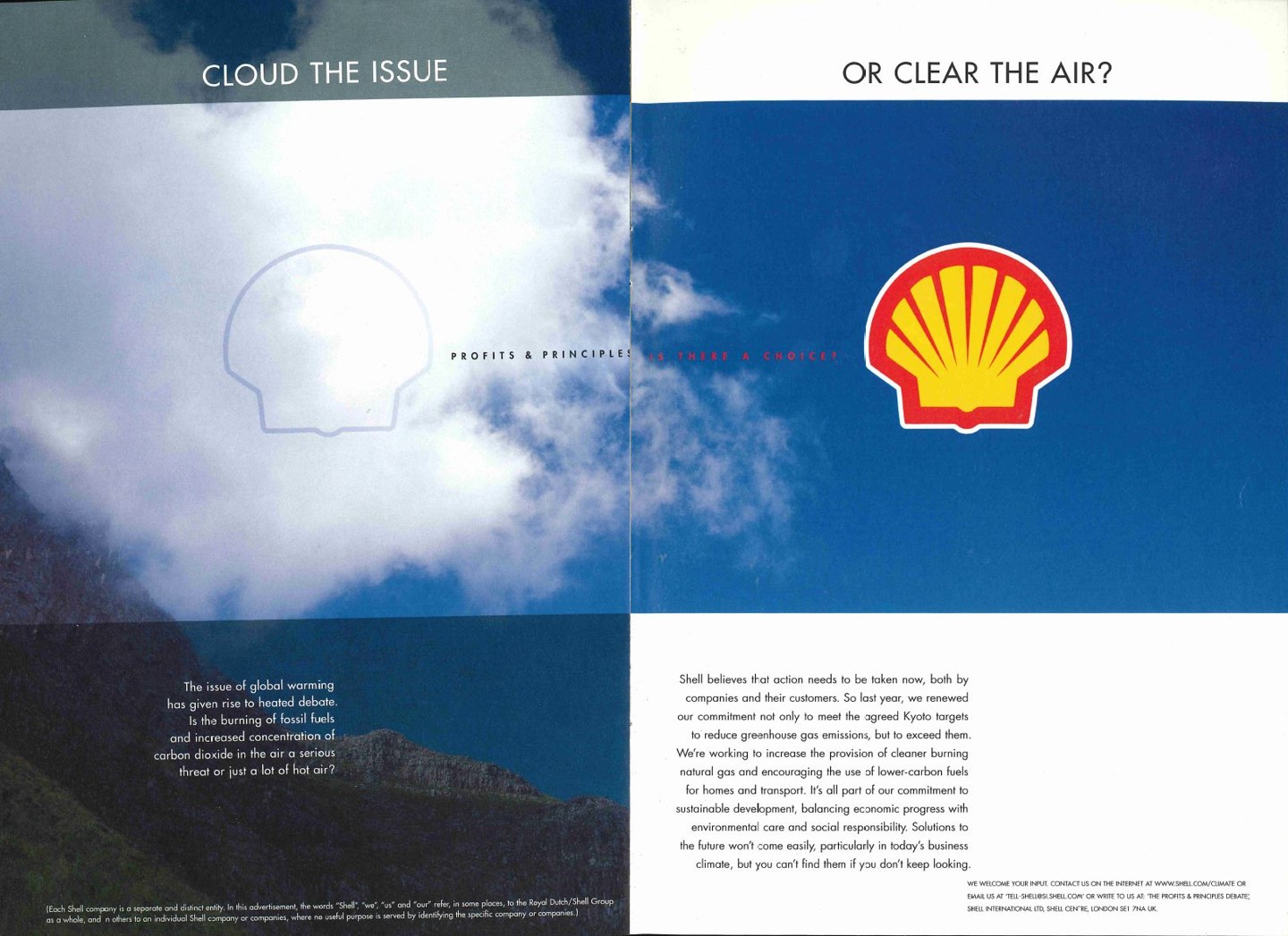

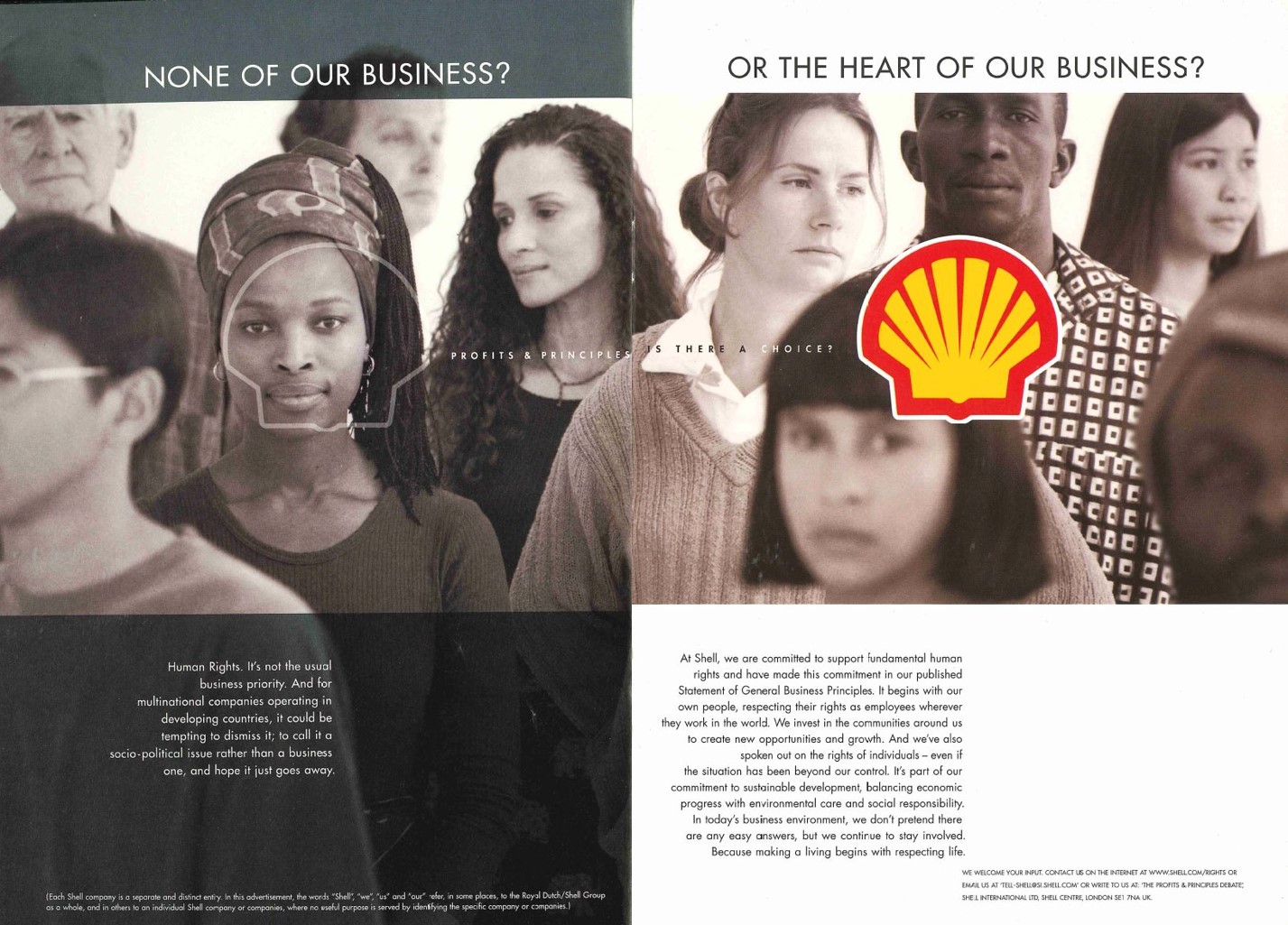

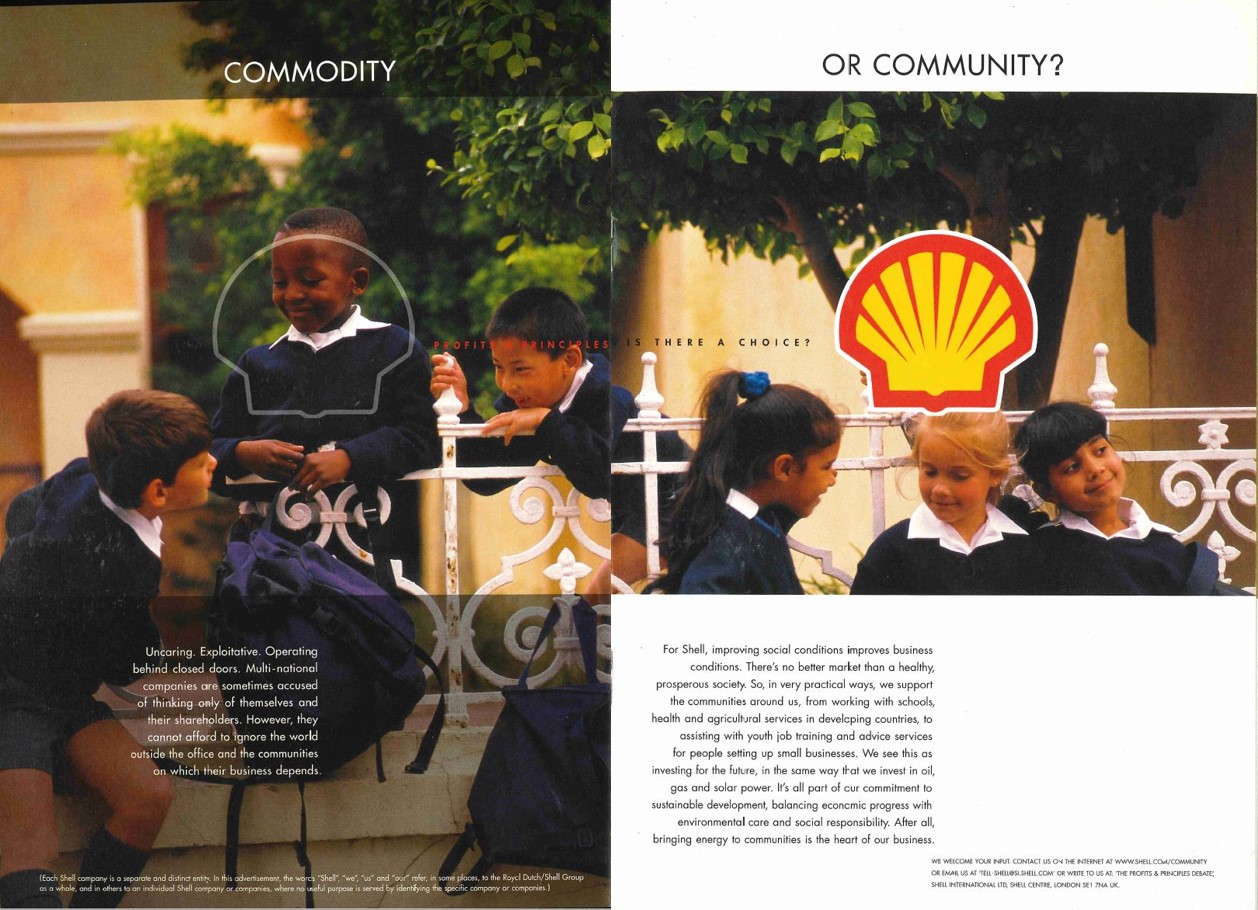

Shell’s 1999 document also promoted the image of the company acting responsibly towards the communities it affects, which campaigners say contrasts with the reality of activities on the ground.

The document recommended Shell doesn’t shy away from issues like human rights and community engagement. It warned fossil fuel companies cannot afford to “ignore the world outside their office and the communities on which their business depends”.

Instead, the document suggested Shell should promote how “we support the communities around us” and frame the company’s community engagement as “investing for the future, in the same way we invest in oil, gas and solar power”.

But such activity is hurdling a low bar in terms of responsible action, Sneirson said. He argued Shell’s adverts commit the “sin of irrelevance”:

“It’s Shell saying ‘We’re not polluting!’ or ‘We’re not killing endangered species!’ or ‘We respect human rights!’.”

“But there are laws protecting the environment and endangered species and human rights so what Shell is really saying is ‘We’re obeying the law!’.”

Shell continues to push this image of the company as a socially responsible actor today, despite allegations of corruption and human rights abuses in Africa, and ongoing efforts to take the company to court over alleged environmental negligence.

Worth, of Culture Unstained, said Shell employs this strategy because changing a company’s image is much easier than changing its practices.

“Shell is pioneering the dark art of corporate social responsibility here,” she said. “Or course it’s hard to look at the innocent faces of those children, the tiny frog held tenderly in the jaws of a tropical plant, the pristine wild places showcased in the adverts without having warm fuzzy feelings and perhaps subconsciously associating them with Shell.”

“But what’s going on here is more subtle. Shell is claiming to be open to dialogue, aware of its mistakes, embracing change, all the things the viewer would hope for; but crucially, without any concrete evidence or commitments that anything’s going to change”, Worth added.

“It has realised that it’s not how it operates that’s important: it’s having a social license to operate, and that can be bought much, much more cheaply”.

History of Greenwash

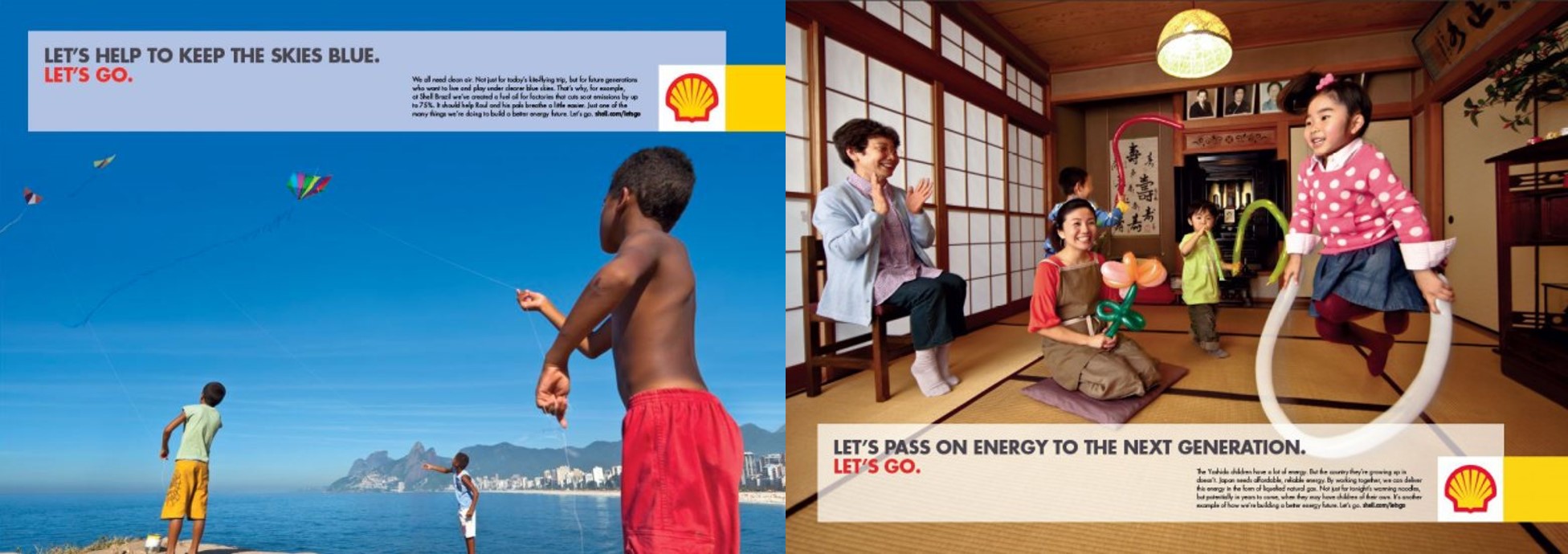

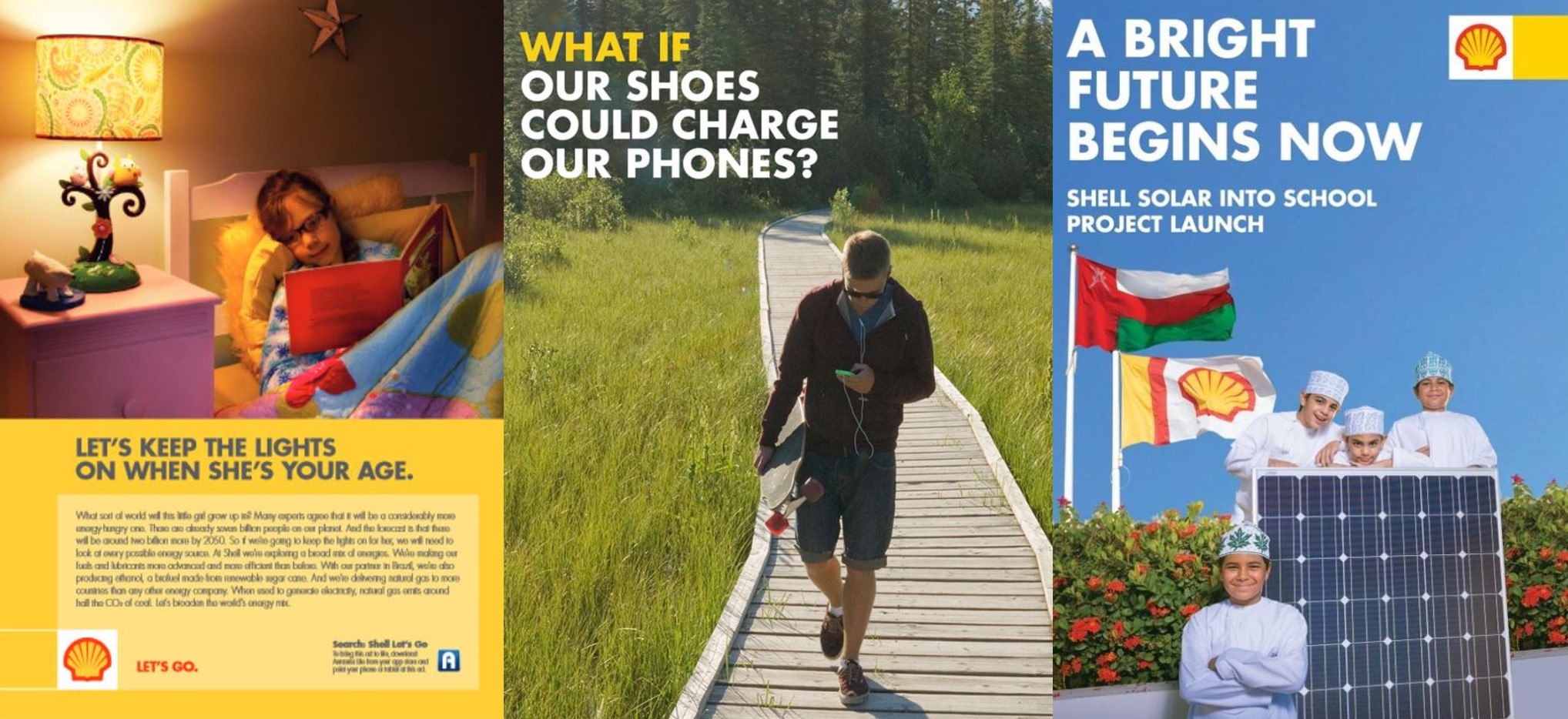

The principles outlined in the 1999 document — of emphasising the positive, and putting people rather than products at the heart of their campaigns — have persisted in Shell’s advertising over the past two decades.

In 2017, Shell won an award for its ‘Best Day of My Life’ TV advert, part of its #MakeTheFuture campaign. The video featured pop stars hailing the quality of life the company could provide through its products:

This relentless focus on a better, more efficient, future can also be seen in Shell’s adverts throughout the 2000s.

The publicity campaign is perhaps not a fair reflection of Shell as a company, Sneirson said. The adverts fall foul of the “sin of false labels”, he argued.

“The images in the ad — blue skies, beach sunsets, lush forests — are meant to suggest Shell is pro-environment, and you should ignore whatever negative things you may have heard or read about the company,” he said.

But the company’s attempts to promote a clean, green, vision of itself has tripped it up in the past.

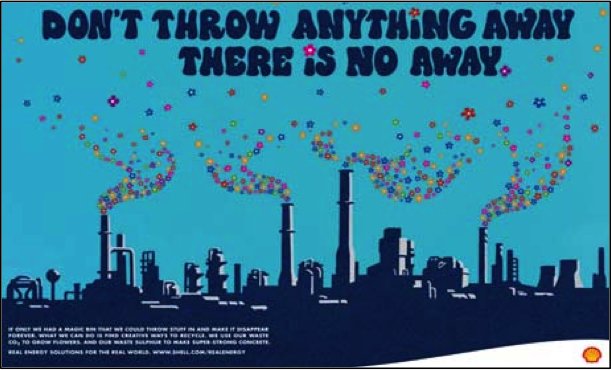

In 2007, the Advertising Standards Agency ruled that Shell misled the public in one advert that implied some of the emissions from its fuels were recycled:

And in 2010, Greenpeace successfully fooled much of the media with its parody of Shell’s “Let’s Go” advertisements.

The campaign group mocked up a website, held a fake launch event, and produced a series of its own adverts with Shell branding but very off-brand messages, which went viral.

That hoax reminded the world that whatever image Shell may try to push, it is still an oil company at heart.

Bob Brulle, a professor of sociology at Drexel University who has long studied the fossil fuel industries’ communications strategy, told DeSmog UK that companies needed to be held to account over their advertising.

“The PR campaign from Shell is very typical of corporate promotion campaigns. These sorts of campaigns are one sided amplifications of corporate activities to attempt to improve corporate reputation. The crux of the issue is whether the campaign is actually followed through”, he said.

He pointed to Shell’s growing emissions as evidence that the company was not meeting the standards implied by its own advertising.

Worth said she was amazed things have evolved so little in two decades. Pointing to Shell’s ongoing deals to sponsor museums, schools and sports clubs, she said:

“These days, our cultural institutions and learning spaces have become oil companies’ advertising billboards of choice, where they push many of the same misleading messages as they pioneered in 1999.”

“Shell’s playbook remains surprisingly unchanged today. Anyone would think, from looking at its current #MakeTheFuture campaign, that the company would have largely transitioned away from fossil fuels by now.”

Yet, it hasn’t.

While its advertising strategy may imply a commitment to a low carbon future, Shell’s business model remains stubbornly fossil-fuelled — despite what it has known about climate change for decades.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts