Our epic history series continues with a look at Lord Lawson’s muddled account of when he first came to talk about climate change.

“The first time I broached the matter [of climate change] in public was in the course of a lecture I gave at the London School of Economics [LSE] in 2004,” the climate denier Lord Lawson recalls in the updated edition of his autobiography, Memoirs of A Radical Tory.

The Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) founder writes: “The concern I expressed about climate change in my 2004 lecture was that the Treasury had, unaccountably, not been asked to make a dispassionate economic assessment of the issue before the hugely costly commitment to the rapid decarbonisation of the British economy had been made – not even the most elementary form of cost-benefit analysis. That would certainly not have been permitted in my day.”

Slightly Muddled

Lawson tells those who ask that: “After that [the climate sceptic economist] David Henderson, who I had known for many years and who had been taking an interest in the subject for some time, starting talking to me about this. And as I said in the dedication, he was to arouse my interest but it was actually after I made this speech.”

But, old Lawson has his own story of coming to the climate debate slightly muddled. His talk, titled “Challenging the Consensus” was delivered at 6.30pm on Monday 15 November 2004. He had, in fact, already broached the issue of climate change in the House of Lords in the spring of 2004.

As Henderson recalls: “Early in 2004, our joint cause acquired a notable ally when I convinced a former chancellor to the exchequer, Nigel (Lord) Lawson, that climate change issues deserved his serious attention.”

At this time, Fred Singer, head of the sceptic Science and Environmental Policy Project (SEPP) in the United States, was already promoting Henderson and Ian Castles, former secretary of the Australian Government Department of Finance, in their attack on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Henderson persuaded Lawson to support his criticisms of the IPCC statistics in the House of Lords.

IPCC Economics

It all began with Lord Taverne, who rose to his feet at the House of Lords in April 2004 and asked Baroness Farrington of Ribbleton whether the British government was satisfied with the economic and statistical work of the IPCC. His concerns were based on the critique of the IPCC set out by David Henderson and Ian Castles.

He said: “My Lords, does the minister agree that forecasts of global warming depend not only on scientific forecasts but on economic forecasts? Is the department aware that some extremely pertinent criticisms have been made of the special report [on] emissions scenarios by two very distinguished economists – Mr Ian Castles, the former head of Australia’s Bureau of Statistics, and Mr David Henderson, the former head of the economic division of OECD?”

Lord Lawson was dissatisfied with Baroness Farrington’s response and joined the attack.

“Lord Taverne has put his finger on what is potentially a major scandal,” he weighed in. “Under the flawed proceedings of the IPCC even the lowest emissions scenario, which leads to the lowest extent of projected global warming, is based on a rate of growth of the developing countries in the coming century that is far faster than has ever been known.

“As a result, by the end of the century under its projections, the average income of Algerians, South Africans and North Koreans will be higher than that of the citizens of the United States.

“Is the noble Baroness really content that this very important matter on which major policy and public expenditure decisions have to be taken should be left to what is little more than an environmentalist closed shop that is unsullied by any acquaintance with economics, statistics or, indeed, economic history?”

Faulty Methodology

Singer certainly noticed the short contribution and, a few days later, copied the extract from the Hansard official record of Parliamentary proceedings and emailed it to members of the SEPP in the US.

Singer told his loyal readers: “The noble Baroness is wrong. The Castles–Henderson critique is not about the forecasting per se but about the faulty methodology employed.”

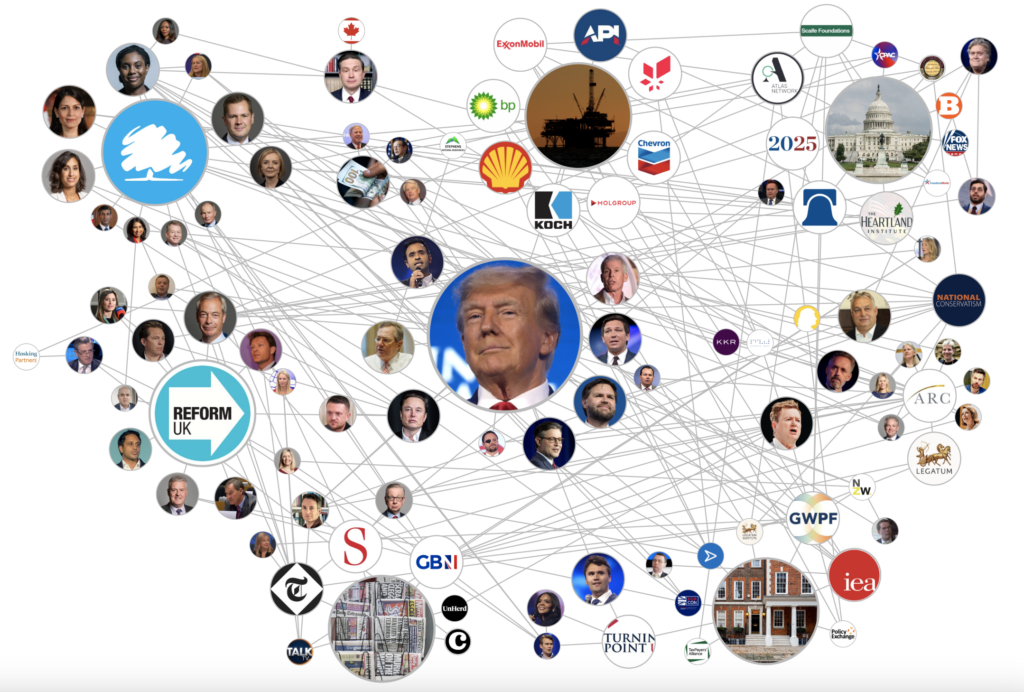

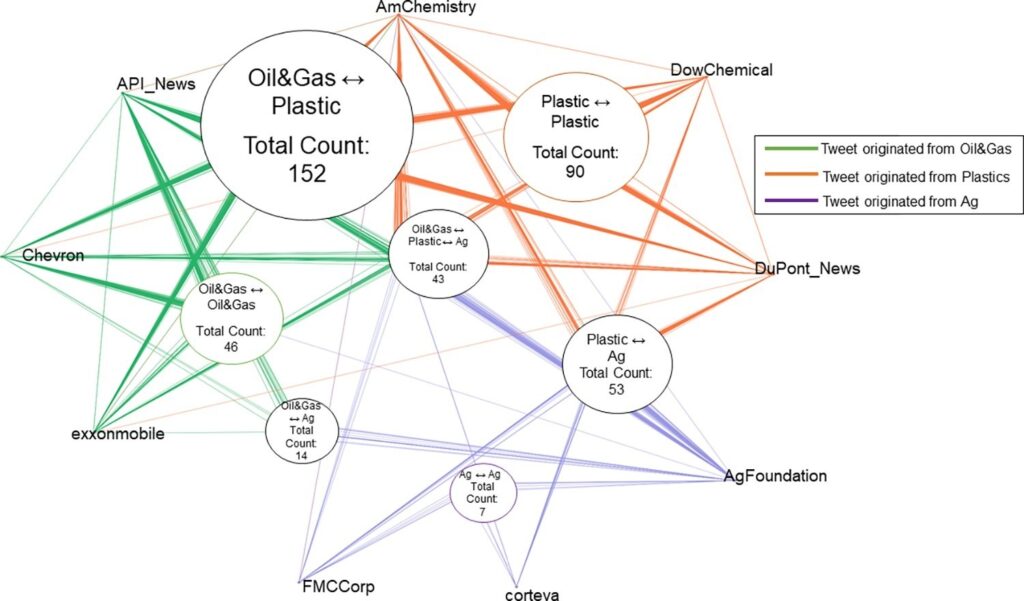

By September that year, it seems that Lawson had already begun working with Julian Morris at the Exxon- and Koch-funded think tank – the International Policy Network (IPN) – and Henderson and Colin Robinson of the tobacco- and oil-funded Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA).

Henderson then convened an “economic group” with a series of meetings at the Westminster Business School. This would arguably prove to be the nucleus of the future GWPF.

Secret Meetings

But, Henderson refuses to answer questions about the economics group; Peiser, as GWPF director, says that these meetings were secret, and Lawson denies that Henderson was a founder of the charity.

Peiser told me: “You are the last person I would discuss these kind of private meetings before we set up. They were private meetings. They were meetings that obviously discussed the GWPF, but I am not prepared to talk about them with you or anyone else.”

Some insight may be gained, however, from Sir Ian Byatt, who attended those early meetings having known Henderson since they both studied at Oxford together. They enjoyed regular luncheons at the exclusive private members’ Oxford and Cambridge Club in Pall Mall during which he was invited to attend.

Sir Ian told me: “I see him [David Henderson] as the impresario, the intellectual Diaghilev who brought together the stars – in Diaghilev’s case Stravinsky, Nijinsky and Picasso, in David’s case Lawson, [Richard] Lindzen and [Ross] McKitrick.

“David has, throughout the debate, stressed the importance of looking, rigorously and professionally, right across the board, at the ‘science’ as well as the economics, and the culture… Compared with David’s standard, the work of many economists (and others) is deficient; insofar as they ‘accept the science’, neglecting the uncertainties in the scientific analysis and their interaction with other uncertainties… Like other practical people, such as doctors, we must always be careful to avoid the cure being worse than the disease.”

Group Demands

Henderson’s economic group collaborated on a letter to the Times that September which was, once again, eagerly sent around the US sceptic community by Singer.

The letter accused both Prime Minister Tony Blair and the Conservative opposition leader, Michael Howard, of being of “one mind” and holding “the same alarmist view of the world” and calling for “the same radical – and costly – programme of action.”

They had given too much credence to “sombre assessments and dark scenarios” while ignoring the uncertainties of climate science.

Lawson and his co-signees warned darkly that climate policies would “raise costs for enterprises and households, both directly as consumers and as taxpayers. They would make all of us significantly and increasingly worse off.”

They concluded by demanding the Treasury step in and stop such expensive government policies. A month later, Lawson was again able to air the group’s concerns in the House of Lords.

Blood-Curdling Warnings

“My Lords, does the noble Lord agree that the prime minister’s blood-curdling remarks about the imminent threat to the people of this country from global warming are probably about as well founded as his earlier remarks about the imminent threat to the people of this country from weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?”

He went on: “Before any further speeches are made or action taken, would it not be a good idea if the prime minister asked his close friend and loyal colleague the chancellor to instruct the Treasury to undertake a thorough cost/benefit analysis of this difficult issue?”

Lord Whitty, then the Labour Parliamentary under-secretary at the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), responsible for sustainable energy, hit back: “To call warnings about global warming ‘blood-curdling’ seems to me the height of irresponsibility.

“I am surprised at the noble Lord, Lord Lawson. This is one of the major problems facing the world. It is important that we tackle it in a cost-effective way. The Treasury and the chancellor have been very involved in developing the best policy measures, support systems and R&D in order for us to be at the forefront throughout the world in tackling climate change.”

Lawson’s Speech

Only after his sharp interventions in the House of Lords did Lawson speak at the LSE. The speech outlined his time in office but then, unprompted, he moved onto the issue of climate change.

He claimed that both Defra, in Britain, and the IPCC had a “vested interest” in exaggerating the threat of climate change, while Blair had “something of a penchant for apocalyptic warnings based on flimsy evidence.”

The atheist then set out his theory that climate change had replaced religion in the new secular world, especially in Europe: “People still feel the need for comfort that the transcendent certainties of religion can provide, and it is what might be termed the quasi-religion of greenery which has filled the vacuum, with reasoned questioning of any of its mantras regarded as a form of blasphemy.”

Lawson, a member of the Economic Affairs Committee in the House of Lords, then persuaded his colleagues to hold an investigation into the economics of climate policy. He writes in his autobiography: “This enabled me to begin seriously to educate myself about the subject, in the course of which I discovered, inter alia, that important aspects of the science were far from certain.”

Sceptic Attention

This Parliamentary hearing would be the first time that British sceptics had been taken seriously by any part of the establishment. The fact that the British establishment was even discussing the lurid allegations of the sceptics would play well in the US, where an upper crust accent and the historic seat of democracy can lend credence even to the conspiracy theory of weapons of mass destruction.

Four days after Lawson attacked climate science at the LSE, Henderson, his new mentor and advisor on climate, was the all-expenses-paid guest of the US-based Exxon-funded free market think tank, the Marshall Institute.

Speaking at a Washington Roundtable on science and public policy, entitled “Are the IPCC’s Global Warming Forecasts Based on Faulty Economics?” Henderson told the audience: “You can act directly if you know any of these officials – and I gather many of you here are staffers – by persuading people in the legislature that these agencies and departments should be involved, so they will bring pressure on these economic and statistical agencies and departments.”

He concluded: “The stakes are high… you have a better chance of success in this city than people like me have with the British bureaucracy.” Henderson is a former professor of economics at Oxford University with an insider’s knowledge of the civil service.

Having felt himself ignored and attacked by Rajendra K. Pachauri at the IPCC, he found himself welcomed into the warm embrace of the army of free market think tankers in the US, eager to recruit such able men to its ranks.

Next time, our DeSmog UK epic history post will look at how Julian Morris’s free market think tank spread its influence in its attack on the Kyoto Protocol.

Photo: The Guardian via Creative Commons

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts