Shell, one of the world’s largest oil companies, has gained privileged access to the UN climate change negotiations while pushing the same unworkable solutions for almost 20 years, internal company documents reveal.

DeSmog UK has previously reported on a tranche of documents first unearthed by Jelmer Mommers of De Correspondent published on Climate Files, that reveal Shell knew about the causes and impacts of climate change since at least the 1980s.

Analysis of these documents, combined with new sources freshly uncovered by DeSmog UK, shows that while Shell’s understanding of the science developed, its proposed solution to the problem has remained remarkably static.

The sources also reveal how Shell uses trade associations to gain privileged access to the annual UNFCCC climate negotiations, despite the organisations’ professed independence.

Carbon Markets + CCS = Fossil Fuelled Status Quo

For almost two decades, Shell has pushed the same proposal to tackle climate change, which still hasn’t come to fruition — a global carbon market plus carbon capture and storage.

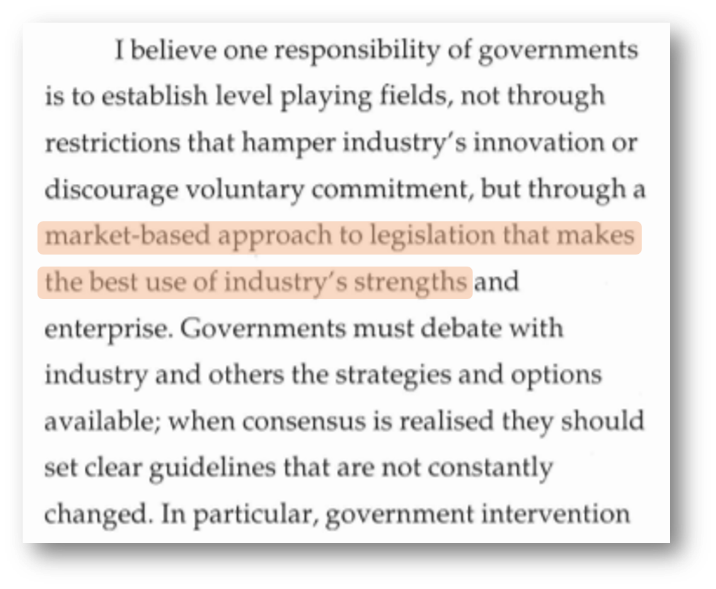

As early as 1992, Shell was calling for “market-based” solutions to ramping up renewables and cutting carbon dioxide emissions from the energy sector:

But it wasn’t until 1998 that it officially put this forward as a proposed solution:

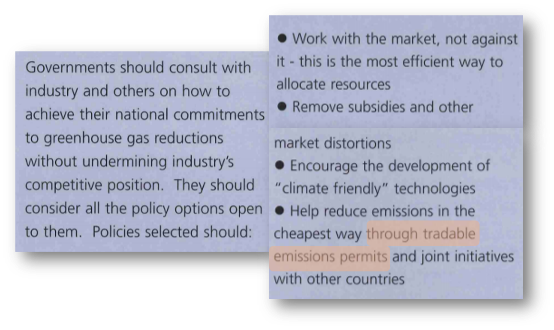

It called for governments to work out a system of “tradeable emissions permits” — a reference a carbon market where companies can buy permits to emit if they go over their allowance and sell any permits they may have spare if they emit under their allowance.

While a carbon price and wide-reaching carbon markets could help cut emissions, analysis from campaigners at NGO Corporate Accountability International suggests they currently just “displace attention from real solutions”.

They argue that while the markets could work in principle, in practice they consistently failed – preserving the status quo, with the EU’s much maligned emissions trading scheme is an oft-cited example.

More recently, the calls for carbon pricing and markets have been combined with pleas for greater investment in carbon capture and storage technology (CCS), which sucks emissions out the air and locks them away. The technology theoretically allows fossil fuels to be burned without harming the climate, but it remains unproven at scale.

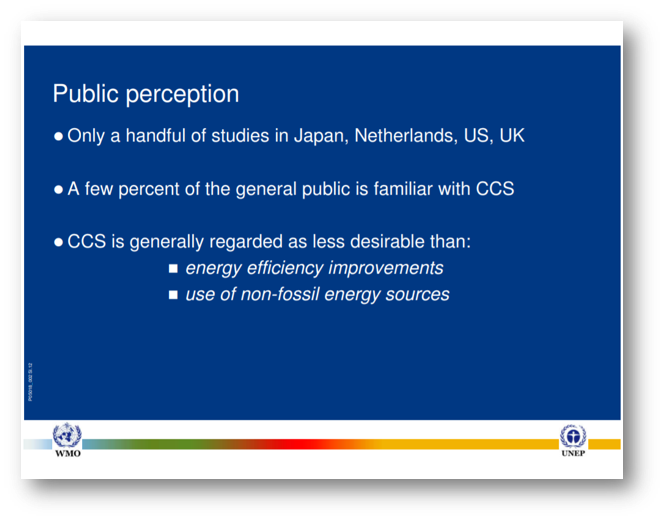

In a document newly uncovered by DeSmog UK, a Shell analyst, Wolf Heidug, presented the case for CCS at a panel during the UN’s annual climate meeting in Montreal in 2005:

In his presentation, he expressed concern that CCS was considered “less desirable” than solutions that didn’t fit with Shell’s business model — including “energy efficiency improvements” and “use of non-fossil energy sources”.

Heidug made his presentation at an event to introduce the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s new special report on CCS, on which he was an author, and which counted three Shell employees among the reviewers.

This approach — calling for the roll out of carbon pricing and markets, while investing in CCS, and continuing to burn fossil fuels in the name of ‘development’ — persisted for another decade.

In a 2014 presentation by David Hone, Shell’s chief climate change advisor, newly uncovered by DeSmog UK, one slide points out that CCS is necessary because without it the world will have to “stop using fossil fuels”.

“But what about growing energy demand”, it pointedly asks.

Another presentation in 2014, by Tim Bertels, Shell’s Head of CCS, has a slide echoing many of the concerns Heidug had raised almost a decade before. “Public Support Must Be Addressed”, it says:

It suggests this could be done through “transparency on the options available to reduce GHG emissions, and their costs” — possibly a reference to a need to talk about the costs of renewable technologies.

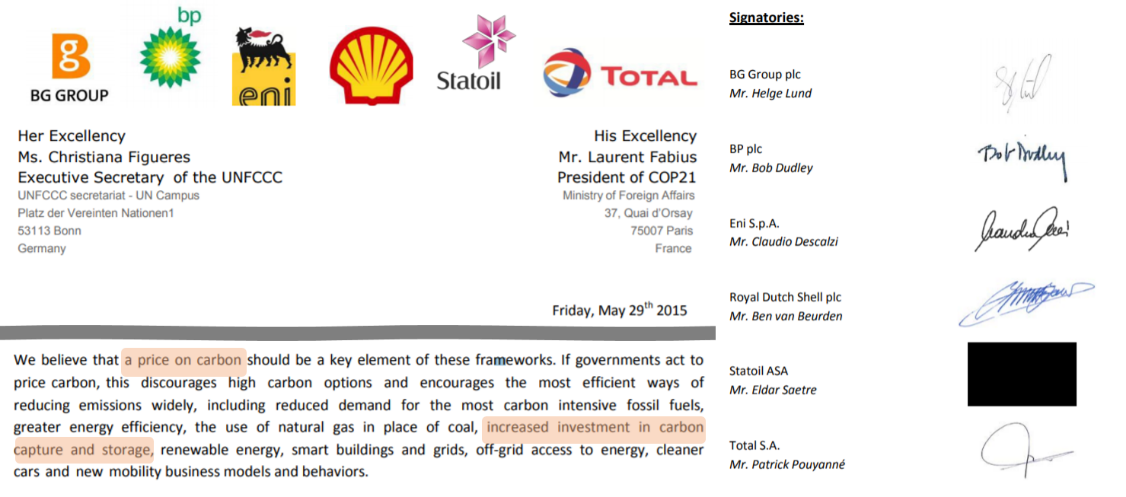

Shell’s lobbying for this approach was in full force ahead of the landmarket Paris climate change conference in 2015.

In a letter from Shell and five other fossil fuel companies to the UN Climate chief and president of Paris meeting, the companies called for “a price on carbon” to be a “key element” of the eventual Paris Agreement. The letter also promoted “increased investment in carbon capture and storage”:

The company’s call for such schemes is normally accompanied by the assertion that fossil fuels will remain a crucial part of the energy system for decades to come, mainly as a means to alleviate poverty.

As Mark Moody-Stuart, Managing Director of Shell Transport and Trading Company told the Society of Petroleum Engineers in 1994:

This attitude persisted for more than a decade, with a newly uncovered internal magazine framing the climate change problem ahead of the landmark Copenhagen climate conference in 2009 as one of providing “affordable energy” and cutting emissions — with the emphasis firmly on both aspects:

And Shell persists with this approach today.

The company denies that it had any special knowledge about climate science that meant it should have changed its behaviour earlier. And it continues to assert that fossil fuels are justified as a means to alleviate energy poverty. A spokesperson for Shell told DeSmog UK:

“We have long recognised the climate challenge and the essential role of energy in driving the world’s economy, raising living standards and improving lives. Yet there are still over 1 billion people in the world without safe, reliable access to energy or the basic benefits it provides. Society therefore faces a dual challenge of meeting growing demand for energy, while at the same time transitioning to a lower carbon world”.

Why is Shell continuing to lobby the international negotiations to adopt this solution today, despite 20 years of failure?

Corporate Accountability’s reports say that even in 2018, fossil fuel company’s emphasis on carbon markets and CCS at the negotiations distracts from “the meaningful, real solutions that harbor the greatest potential to justly curb the climate crisis.”

Trade Associations as Front Groups

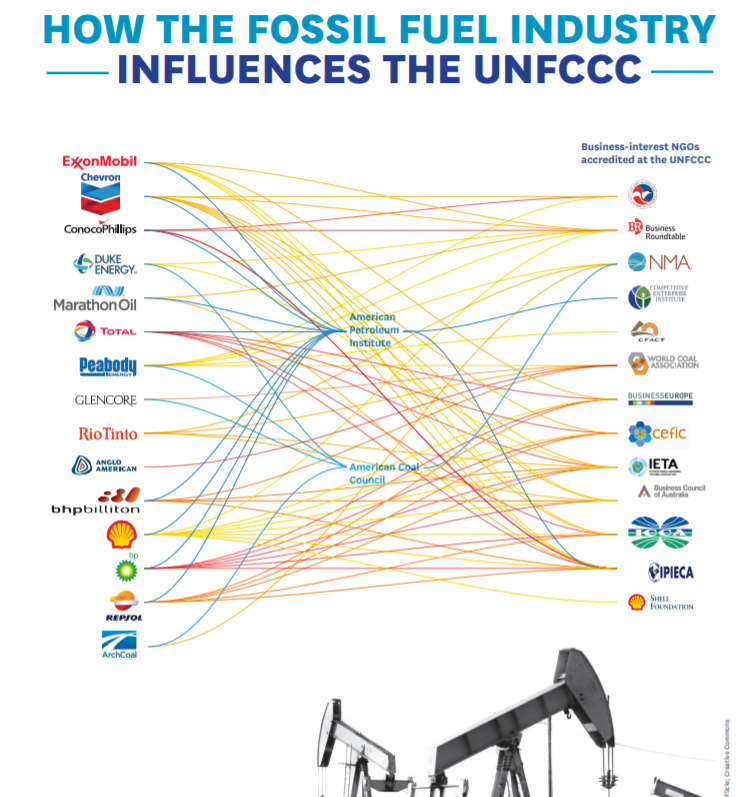

Despite Shell and other fossil fuel companies’ clear economic incentive to slow the progress of action on climate change, they continue to get privileged access to the talks through trade associations.

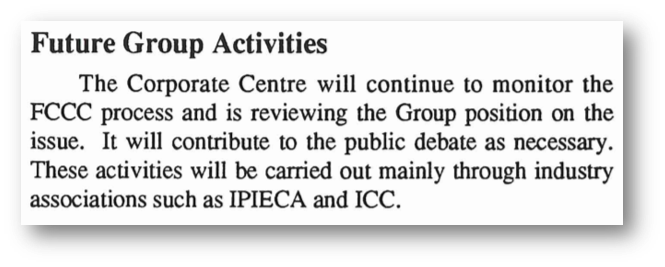

As early as 1996, Shell was tracking the international negotiations and research from the scientific advisors to the process, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), closely. In a document summarising the IPCC’s major second assessment report, the company pledged to continue to have its say in the international climate negotiations using trade associations:

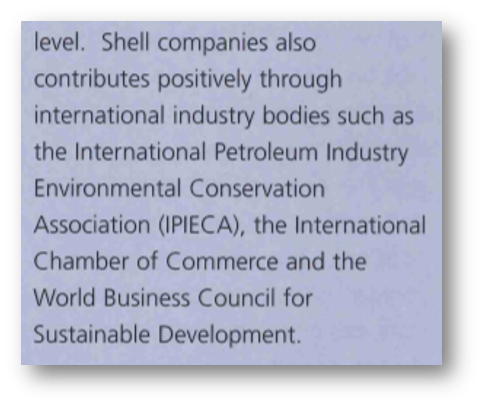

Futhermore, in a 1998 document titled “Climate change: What does Shell think and do about it?”, it points to the “positive contribution” the company had on international negotiations through such groups:

The groups named by Shell in the 1990s are still participating in the UN Climate conferences today.

Both the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) are “official observers” to the UN Climate conferences, meaning they are allowed inside the main negotiating area.

IPIECA’s website claims it “does not lobby on behalf of the industry, but aims to increase understanding and provide timely information to members and key stakeholders”. But Shell’s decades-long commitment to having its voice heard through the organisation — as revealed in the documents — would appear to contradict this.

WBCSD is less cautious. Its website says: “We aim to be the global voice of forward-thinking business in influential international forums, particularly in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).” This includes providing resources for policy makers, including a guide on ‘Why Carbon Pricing Matters’.

Both organisations have been on campaigners’ radar for years. Corporate has long asserted that such groups allow fossil fuel companies to become “deeply embedded in the treaty process”.

Jesse Bragg, media director for Corporate Accountability, told DeSmog UK:

“Unfortunately, these findings just reinforce what the movement to kick Big Polluters out has been pointing out for years: these trade association are just doing the bidding of the world’s dirtiest polluters. It also bolsters the call from governments to initiate a process within the UNFCCC to finally address the undue influence of groups like IPIECA and WBCSD in climate policy.

Such findings give governments all the proof they need to show IPIECA, WBCSD and other trade associations representing Big Polluters the door. Their participation in the UNFCCC is entirely illegitimate and is at odds with the objectives of both the IPCC and the UNFCCC.”

The documents show Shell knew about the dangers of climate change for decades, and has had privileged access to the UN Climate negotiations from their inception outset. Yet, the company has continued to push an unworkable solution for more than 20 years— all while continuing to extract and sell the fossil fuels driving the climate crisis.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts