It was a crisp, bright day in February 2017 when politicians, academics and business figures came together to discuss the problems of the Scottish fossil fuel sector. A year before, world leaders had thrown their weight behind a clean energy transition with 195 countries signing the landmark Paris Climate Agreement. Six months after that, the UK had voluntarily ramped up its own emissions reduction target.

But this meeting was different. It was convened to explore how the UK could keep the North Sea’s oil and gas industry going, not wind it down. The Scottish energy tycoon Sir Ian Wood summed up the mood when he declared the industry was “nowhere near the end of its life”.

Can Scotland really have it both ways? Is Aberdeen preparing for the low carbon future the UK and the world is promising, or is it still investing in a future where oil and gas remain the spine of its economy?

This DeSmog investigation reveals a region that continues to put the industry at the heart of its economic planning. In the energy, education, and transport sectors, Aberdeen and its surrounds continue to build on the basis that oil and gas is the future, making the gamble that climate policies won’t make the industry a relic of the past.

A Fossil-Fuelled Future

Since the oil price crash of 2014, in separate silos of conversation to that of UN climate talks and national emissions targets, the oil and gas sector in the Scottish north east has been working hard to buoy their once profit-churning industry. Both the UK and Scottish governments have been keen to help too, ostensibly to protect jobs and tax revenues, offering no shortage of tax breaks.

And the government-industry duo has largely succeeded, with a flurry of business in the past 18 months that some have even referred to as a ‘North Sea renaissance’.

Notably, this has often been achieved through what the industry nebulously refers to as ‘cutting costs’ and ‘increasing production efficiency’; explanations which, on the ground, have frequently amounted to suppression of worker’s wages, with ensuing acrimony and even strikes in tow.

The 2017 meeting in Aberdeen, the city at the heart of the UK’s fossil fuel wealth, was for the opening of the Oil and Gas Technology Centre (OGTC), an £180 million innovation venture tasked with supporting oil and gas companies. Money came from both the UK and Scottish governments as just one part of a network of measures designed in the past few years to extend extraction in the nearby North Sea.

Some have suggested that the work of the OGTC could unlock 3.5 billion barrels of new oil – equivalent to around six years’ worth of what the industry is currently pumping out.

Far from looking at how to make a just transition to a low carbon economy, state-led industry protection like this was called for following a 2014 paper by Sir Ian Wood which laid out a vision for how the North Sea could continue to prosper well into the future.

The paper set a new tone of conversation for the sector and, in the face of fluctuating oil prices and increased international competition, coined what’s now a mantra for both government and industry – maximising recovery from the North Sea.

Elsewhere, on the same day as the OGTC’s opening, the Department of Transport released a research paper on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from road freight. More widely, the government was under pressure to make a legally binding commitment to ‘net zero emissions by 2050’, meaning it wouldn’t be able to emit more carbon than it offset elsewhere.

How can these policy contradictions sit so comfortably next to each other?

Last year researchers at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research carried out a report for Friends of the Earth Scotland which showed that 70-80 percent of Scotland’s existing fossil fuel reserves must be left in the ground for Scotland to fulfil its obligations under the Paris Agreement. How do industry oil and gas handouts fit the science?

Asher Minns, head of Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research said: “One of the many climate and sustainability policy challenges is lining-up the policies so that they are complementing rather than pulling at each other.”

Policy contradictions are nothing new, and are not unique to climate and energy policy. But the kind of regressive expediency fed by the UK’s oil wealth could be seen clearly when Kirsty Blackman MP for North Aberdeen told the House of Commons in 2015: “From a small airport through to traffic congestion and limited housing stock, Aberdeen has struggled to keep up with the demands of the oil and gas sector.”

To the casual observer, it would seem that Scotland’s climate policy commitments and the reality of its infrastructure decisions are an example of a country’s right hand not knowing what the left is doing — or being wilfully indifferent to it.

Roads to Nowhere

“Our response to the climate change emergency must be comprehensive and consistent,” said Sam Gardner from WWF Scotland. “And yet we’re still seeing decisions being taken leading to ‘high’ and ‘low’ carbon infrastructure, or a ‘green’ and ‘black’ economy.”

One example of this well-known to inhabitants of Aberdeenshire is the decades-long saga of the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR), a 26 mile stretch of bypass road around the city.

Aimed at reducing congestion, the AWPR was first mooted in the late nineties and given the go ahead in 2003. A string of court challenges caused significant delays to the £745 million project, of which the final stretch opened in February 2019.

As with many infrastructure issues in the north east of Scotland, the oil and gas sector was at the forefront of the decision. A 2012 Scottish government document said that the road would bring an estimated cost reduction of two percent to the oil and gas sector just five years after completion.

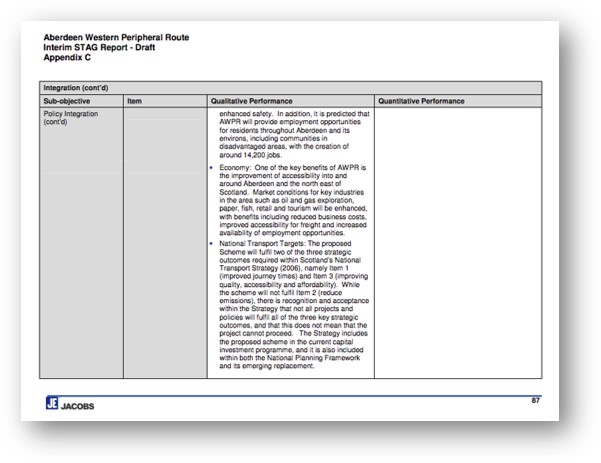

“One of the key benefits of AWPR is the improvement of accessibility into and around Aberdeen and the north east of Scotland,” the document says. “Market conditions for key industries in the area such as oil and gas exploration, paper, fish, retail and tourism will be enhanced.”

Image: An appendix from the Jacobs report on the AWPR

Separately, the Scottish Government claimed the road would help indirectly attract an additional £6 billion to Scotland’s north east economy and create 14,000 jobs over the next 30 years.

But these figures came under fire recently as their calculations were based on figures from before the 2008 financial crash, when Aberdeen had a growing fossil fuel sector fuelling its local economy.

North East conservative MSP Tom Mason lambasted the lack of an update to this modelling as “naive economics”, suggesting that the road’s financial justification relies on outdated projections of a burgeoning oil and gas sector.

“It seems they have taken a gamble and it’s my sincere wish these sums won’t look foolish in another 30 years,” he added.

But beyond being built on the promise of an industry that – in theory at least – the government is meant to be rapidly shutting down, the road also has a more basic symbolic problem: building a big road encourages more cars, which emit more carbon dioxide.

That’s why, broadly, the project has been opposed by environmental groups and some local politicians, as the £745 million project has deflected vital funds from long-term sustainable transport.

Gardner said the government still thinks high-carbon decisions can be justified by mitigation elsewhere. “But we must commit to only investing in and supporting net zero solutions,” he said. “Anything else is simply an exercise in increasing risk and placing costs on the next generation who will be faced with the burden of stranded assets or the costs of retrofit.”

Image: Press reports criticising economic justifications for the AWPR.

Martin Ford, a Scottish Green Party councillor for the of Aberdeenshire Council, has been a vocal opponent of the AWPR for years. “It is an opportunity cost,” he said. “In that we could have invested in sustainable public transport which would have been good for us right on into the future, as opposed to a 1950s transport solution of building a new and bigger road.”

One of the central problems is that the government makes estimates of how many more people there will be on the roads in the future, and then makes its investment decisions based on these figures. This goes against the rationale of a sustainable transport transition, campaigners like Transform Scotland argue, where policy makers should be steering people away from car journeys and toward more public transport and active travel.

The costs for the new AWPR have escalated dramatically over the years. In 2005 the Scottish Government forecast this to be around £295‑395 million before raising it to £703 million in 2012. The final sum sits at £745 million.

Research by Transform Scotland has shown that, since 2011, road spending has seen a 34 percent increase in spending while aviation has seen an increase of 70 percent. Meanwhile in the year to the Scottish government’s 2017-18 transport budget, funding for bus travel fell by three percent. The overall result of these trends is a tiny two percent fall in transport emissions since 1990, and annual increases in recent years. The Committee on Climate Change has said that overall UK transport emissions must fall by 44 percent between 2016 and 2030.

Under the environment section of the public page for the AWPR, the government even states that the new road “will provide a fast, direct link to Aberdeen Airport” that will “increase the airport’s catchment area and potentially lead to inward investment, including new airlines and routes coming to the city.”

Increased flight traffic – one of the major obstacles to a low carbon future – has rarely been used as an environmental justification for an infrastructure project.

“Essentially, this doesn’t deliver on the stated transport policy of modal shift to public transport, cutting carbon emissions and all the rest of it,” Ford said. “If you test it against those propositions, it’s probably overall perverse and it certainly doesn’t take you further forward. So why not do something else which does deliver on what you say is your transport policy?”

Campaign groups like WWF agree, and have tried working with the government to provide basic joined-up thinking across the range of its infrastructure decisions, but often without success.

Gardner said part of the problem is that government checks on infrastructure projects like the AWPR often only look at the carbon embodied in construction, not the carbon that will likely be generated as a consequence of its existence.

“It’s when you step back and look at the totality of an infrastructure pipeline – that’s when the contradiction becomes quite stark,” he said.

The Public-Private Complex

Beyond the roads and research centres, campaigners and researchers have argued that pursuing endless economic growth based on infinite use of resources is at fundamental odds with the changes needed to avert climate breakdown.

But Ford said this reality is hard felt in areas where access to housing and basic services are at a squeeze, and smart use of public money is needed to improve people’s lives.

He pointed out that in the Scottish north east, the high wages of the oil and gas sector have sent house prices rocketing over the past 20 years while people working outside those wealthy sectors have struggled.

“We have issues of housing affordability, we find it very difficult to recruit teachers and health professionals from other parts of the UK – all because housing prices are very high,” he said. “Therefore, what looks like a very good salary in many places doesn’t look very good in the north east when you take into account housing costs.”

To help with these issues, City Region Deals were launched by the UK government in 2011 to partner central and local administrations in working together on regional development. In Scotland, they exist between the Scottish Government, UK Government and local government, and are “designed to bring about long-term strategic approaches to improving regional economies” and, ultimately, “transformative change”.

18 have been launched across the UK so far, but in the north east of Scotland, corporations rather than people and the environment are at the centre of these large investment channels.

The 10-year Aberdeen City Region Deal was announced in November 2016, worth £250 million of direct Scottish and UK government funding, and a total of £826 million once private sector investment is included.

But what’s unique about the Aberdeen deal is the presence of a fourth partner alongside the three levels of government in the form of Opportunity North East (ONE), an industry-led and privately funded economic development body.

At the head of ONE’s economic leadership board sits Sir Ian Wood – the oil magnate. What’s been the flagship investment of the Aberdeen deal so far? £180 million toward innovation in the oil and gas sector in the form of the OGTC. Or, as a recent House of Commons Library briefing paper recently explained, “support for the oil and gas industry to exploit remaining North Sea reserves.”

Image: ONE‘s website homepage in February 2019

Aberdeen has a history of putting industry-led bodies at the heart of its public planning, as ONE replaced another body in 2015, the Aberdeen City and Shire Economic Future (ACSEF). ACSEF was a partnership of private and public sector representatives which stated that part of its strategic aim was to “anchor” the oil and gas sector to the north east.

Coincidentally or not, this is the same language used by transport body Nestrans when it supported the AWPR, which it said will offer easier transport of goods for energy firms and will help “anchor” them to the north-east.

Not only do these top-table seats help corporations decide where public money goes, but they also give access to facilitating the deals themselves. Investigations by the Guardian and The Ferret have shown how Scottish financiers sought to make major gains through their involvement in these lucrative public contracts.

Image: The Ferret reveals the cost of private finance projects across Scotland

Oil and gas hasn’t been the only benefactor of the Aberdeen City Region Deal’s millions – there are also high speed broadband projects and innovation funding for other industrial sectors, including the life sciences. So, unsurprisingly, business leaders have heaped praise on the deal’s direction.

But with its flagship aim of benefitting Aberdeenshire as a proxy to giving direct support to the oil and gas industry, Ford said it was controversial in its beginnings.

“Aberdeenshire Council expressed strong views that the City Region Deal should be about the future – diversifying away from oil and towards renewables,” he said.

Ford and other members had argued that propping up a North Sea oil with ailing profits was not only bad for the climate, but short-sighted with regard to Aberdeenshire’s long term future.

“There were earlier iterations of possible inclusions of significant investments in public transport, significant investments in affordable housing, and – though in the end there was money to pay for transport studies, which is a plus – essentially the deal became very much oriented away from reducing emissions or diversifying the economy, and toward prolonging the status quo in terms of energy, oil and gas specifically,” he said.

Ultimately the council’s views seemingly fell below the priority of those business leaders choosing where the public money should go. But was this a case of a wealthy region like Aberdeenshire’s economic demands taking precedence over the pressing needs of national climate policy?

“From my perspective as a member of Aberdeenshire Council, you can turn that upside down,” Ford said. “The council wanted a much more enlightened deal than the government wanted. So it was national policy imposing old thinking on a region that knew it needed to break out of that.”

Renaissance

Thanks to this continued influx of both public and private investment to support the North Sea oil and gas sector, the industry is now doing well after the oil price downturn of 2014.

The Chinese state-owned oil giant CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Corporation), Total and Euroil recently announced the discovery of a new gas field of nearly 250 million barrels of oil equivalent, one of the largest in decades.

If the enormous size is confirmed, it would match a 2008 discovery by Maersk Oil which is expected to start producing gas this year and could provide up to five percent of the UK’s energy – together both these fields may produce nearly 10 percent.

Image: BBC News coverage of the CNOOC discovery.

Maersk said that its operations had been helped considerably by tax breaks which the former chancellor, George Osborne, declared as “a clear signal that the North Sea is open for business”.

But the Maersk project has been criticised not only from a climate perspective by environmental groups, but by centrists and conservatives for the recipient of its profits.

Despite the government reiterating the importance of the North Sea for the UK’s prosperity, only half of the £3 billion development investment will be spent here after large parts of the infrastructure were ordered from Singapore and other countries.

Economic nationalists see such arrangements as bizarre at best, naive at worst.

Friends of the Earth Scotland said that the discovery is “terrible news” for the climate. “It’s high time our governments stopped supporting fossil fuel development, and get serious about planning a just transition away from this industry,” it said in a statement.

But at the same time as the Scottish parliament assesses the government’s new Climate Change Bill, the handouts keep coming. Earlier this month a parliamentary report from Westminster recommended that the government offer a new sector deal to the oil and gas industry, including a fresh £176 million for technology innovation. This is important, the report said, to simultaneously “maximise the recovery of the 10–20 billion barrels of oil and gas” and help “the industry reduce its carbon footprint”.

What’s clear is that arguments for rescuing the North Sea fail by their own logic: what’s seen as protection of the UK’s prosperity via fossil fuel tax revenues has actually resulted in zealous tax breaks, largely benefiting big business in Aberdeen and the other nation’s economies. It’s a fallacy.

But those representatives that stand to gain from the financial success of that fallacy were those meeting together in Aberdeen in February 2017, and are still making decisions alongside politicians now.

In such a situation, that the UK is struggling to meet its climate targets doesn’t really matter.

Main image: Pixabay

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts