Across Europe, right-wing populist parties are picking up votes. In some countries, once-fringe parties have gained enough support to propel them into the halls of national power. But, for most, an easier target has been the European Parliament. And that could matter for climate change.

The UK Independence Party is a case in point. The group, once led by Nigel Farage, has seven MEPs, in contrast to zero MPs in the UK parliament (the breakaway “Brexit Party” has a further eight MEPs). But it is not alone in eyeing Brussels as a potential foothold on the path to power.

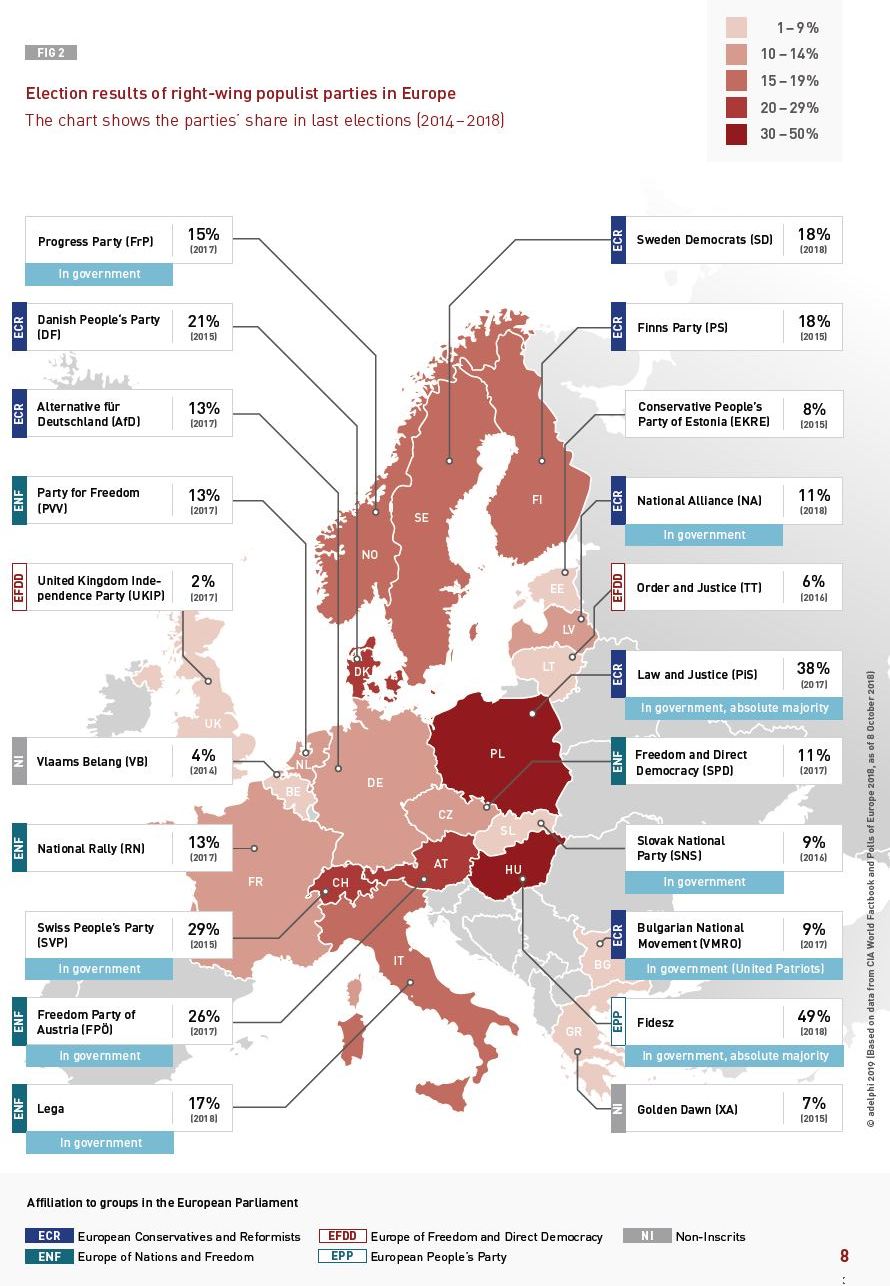

In the 2014 elections, right-wing populist parties took almost 15 percent of the European parliament’s 751 seats. This is predicted to increase in the 2019 elections, scheduled for the end of May. Guy Verhofstadt, leader of the parliament’s liberal alliance, recently warned that the shake-up could usher in a five-year populist “nightmare”.

This means that parties such as France’s National Rally (known as Front National until 2018, when its leader Marine Le Pen decided on a rebrand), the Netherlands’ Party For Freedom, and the Danish People’s Party are suddenly a force to be reckoned with.

“As unprecedented popular discontent obstructs governments in shaping climate policy, the question is whether the EU will be able to maintain its progressive role after the next elections,” write Stella Schaller and Alexander Carius, from the Berlin think-tank Adelphi, in a recent report on rightwing populism and its impact on climate policies.

Over the last two decades, the EU has been a fairly consistent voice in calling for climate action, even if its targets haven’t always matched the urgency of the task. Its goal of cutting emissions by 40 percent by 2030 is deemed “insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker, meaning that if all governments adopted similarly ambitious targets, the planet would warm by up to 3C.

The EU’s climate chief, Miguel Arias Cañete, has already said that the EU is in a position to raise its target and increase its ambition, a move that would have to be approved by the European Council.

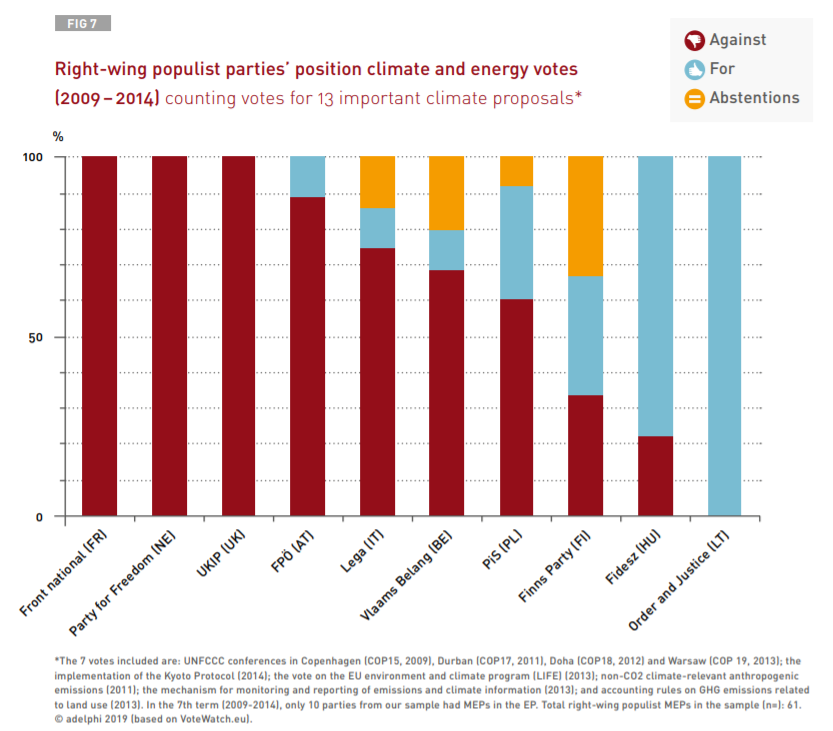

But observers are worried that an uptick in populist MEPs could hinder progress, given that their parties regularly adopt positions denying the science of climate change and opposing renewable energy.

The populists

“Populism” is a somewhat difficult term to define; even harder is describing its relationship to attitudes on climate change.

Both left- and right-wing parties can be populist in nature, yet right-wing parties are more likely to adopt climate sceptic positions. And while they tend to be antagonistic towards attempts to implement climate change policies, many take a decidedly pro-environment attitude to other issues. There are even a smattering of populist parties that support climate action in some form.

“I don’t think populism in itself is a bad thing, if it means you’re in tune with what citizens want. In actual fact, sometimes it’s just about social justice and representing ordinary individuals. [It’s right-wing populism that] is a growing concern, certainly within the EU,” says Lynn Boylan, Sinn Féin MEP for Dublin, Ireland.

Yet when parties do adopt anti-climate positions, they tend to do so based on four common reasons, according to the recent Adelphi report: Reducing emissions is seen among these populist factions as expensive, unjust, harmful to the environment, or simply not worthwhile.

Rather than forming a united front, populist parties are split between the various parliamentary groupings. Fidesz, Hungary’s governing party, is the only right-wing populist party to sit in the more centrist European People’s Party (of which Angela Merkel’s CDU party is also a member). Greece’s Golden Dawn is not affiliated to a parliamentary grouping, and the remainder of the major parties are split between the European Conservatives and Reformists, Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy, and the Europe of Nations and Freedom Group. UKIP and Brexit Party MEPs are split between the Europe of Nations and Freedom Group and the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group.

The groups are also divided by their varied approaches to climate change. While the authoritarian attitude of Hungary’s Fidesz has raised concerns – Viktor Orban, the party’s leader, was famously greeted by European commision head Jean-Claude Juncker with the phrase “Hello, dictator” – it has, at least, publicly supported international climate action. Similarly, Latvia’s National Alliance has argued for multilateral climate action and for investing in clean energy.

Both Fidesz and the National Alliance have been in government for a fairly long time. According to the Adelphi report, this could be one reason for their moderate stances on climate change. Another is the fact that both countries emit less than the EU average, already relying on hydro and nuclear in their energy mixes, and therefore have less to lose by the bloc turning its back on coal.

These pro-climate positions are far from the norm, however, among Europe’s populists. The majority of the parties either outright deny the science on climate change, or else ignore the issue. The Alternative for Germany party and the UK Independence Party are both openly sceptical about the proven connection between carbon dioxide emissions and rising temperatures.

Some parties have a more mixed approach, combining anti-climate sentiment with support for renewable energy. Rather than arguing for these technologies on the grounds that they’ll reduce emissions, they highlight other benefits, including the potential for job opportunities and energy independence. France’s National Rally is a prime example, rejecting the UN’s climate body as a “communist project” while also supporting the development of domestic renewables.

Despite the hostility towards climate change, many right-wing populist parties strongly support environmental policies more generally, which more easily tie into far-right narratives on nationalism, says Bernhard Forchtner, a lecturer in media and communication at the University of Leicester, who specialises in environmental communication by far-right populists.

“If it’s about the protection of the countryside, for example, or biodiversity, this is clearly something to do with the national space. Take the English countryside: we know what it has to look like, we expect it to be populated by these plants and animals, and because of globalisation, because of worldwide trade, species from the outside invade, so to speak, this space. Then there’s a problem,” he says, citing the British dislike for grey squirrels, which almost wiped out red squirrels after being introduced in the 1870s.

Climate change, however, ties in with the populist notion that there is a “global elite telling us what to do,” says Forchtner. “If you frame what’s happening around climate policies in that way, then it can be very easily connected to the populist drama where there are the good people, the evil and corrupt elite, and the far-right actors, who know what the people want.”

Impacts

Support for right-wing populist parties has been surging across Europe. In 1979, these groups had no seats in the European Parliament. After the May elections, they are predicted to make up almost 20 percent of the European Parliament. Many parties have also made headway at the level of national politics, gaining seats and, in some cases, control over government.

The Adelphi report highlights several ways in which populist parties could disrupt progress at the EU level, including hijacking the more ambitious policy proposals. “This not only due to the climate-sceptic attitude itself, but the likely shift of democratic parties’ positions in the fight for votes,” write the authors.

Right-wing populists may also push centre parties into adopting more extreme positions in the search for votes, both at the EU and at the national level, which could threaten climate policy.

Not that this is a strategy that always brings votes flooding over to the mainstream parties. According to Adelphi’s report, shifts in Germany that catered to nationalist preferences in an attempt to attract support from potentially populist voters did “not necessarily result in rising electoral support.”

For Boylan, it’s these centre parties that pose the biggest threat to climate action. “Certainly within the European Parliament, [right-wing populism is] not a big concern in terms of its impact on climate policies,” she says.

“For me, the biggest concern is that those in the centre — particularly in the EPP group or also Alde —though they’re not denying climate change exists, they’re the ones that are actually hampering ambition and stopping us going where we should be going. The right-wing populists are not really having any impact at all because they’re smaller in numbers, though that may change in the future parliament.”

For Molly Scott Cato, a Green Party MEP in the South West, the impact of these parties is already evident in the EU today.

She gives an example on the “taxonomy file”, “which is part of the sustainable finance agenda. So essentially that’s defining what could be a sustainable investment,” Cato said. The climate-related vote brought some unusual suspects into the room, she said. “You could see clearly that people were voting – UKIP MEPs, MEPs from the Front National – that don’t normally vote. So it seems fairly clear the lobby had decided they needed them in the room, and consequently we lost some of those votes by one or two votes.”

Yet, despite the successes of right-wing populists, analysts and politicians are less concerned than one might think about the potential impact on climate action.

“Certainly if they increase their numbers, we will find it harder to take the action we need to on [the Paris Agreement]. I‘m not freaking out about the numbers they might get because, to be honest, there’s a lot of media chat about that and I don’t think we should lose our nerve over it at all,” says Cato.

“It would be a foolish thing to do, to give into fascism, wouldn’t it? Their politics is based on fear and they try to make us afraid, and our job is to be brave, and not be afraid.”

Even among those who are more alert to the potential threat of rising populist numbers, levels of concern about the impact on climate policy are low. The EU’s generally pro-climate attitude, the success of green candidates, and the fact that these parties are still primarily concerned with immigration are all seen as buffers against populist damage.

“The negative vote on climate policy still seems to be quite small in the European Parliament. So I think on this particular issue they would have to get at least above a third of the votes in the European Parliament to really make a big dent. This is not the primary concern for populist parties in Europe. Their main thing is immigration,” says Matthew Lockwood, senior lecturer in energy policy at the University of Sussex, who has examined the link between right-wing populism and climate change..

“It’s also true that, if you look at the European elections, green parties are doing very well. This is the case, for example, in Sweden and in Austria. In some cases, they’re doing better than right-wing parties. When green parties get into governing coalitions, they will tend to go for the environment, energy, climate ministry as a priority,” having a counterbalancing effect to the populists.

What can be done about it?

Despite the rising volume of populist voices in the public conversation – no one can deny the attention lavished upon them in the age of the Trump administration and in the debates leading up to the UK’s Brexit vote – very little research has been done on these parties and their impact on the climate debate.

This lack of information could be hindering efforts to stem the populist tide by politicians and campaigners who are keen to see more ambitious climate change policies implemented across the EU, says Forchtner. To successfully combat populist views, first it is necessary to understand them, he argues, particularly given the nuances and variations that exist between countries.

“What I would like to see is more research that looks at how many of these actors are still outright climate sceptics and how many just use this populist discourse strategy to position themselves with the common man against the global elites,” says Forchtner.

“There’s an ethical issue: If we write something about them, if we say something about other people, I think we should at the starting point take seriously what the other person says. There’s a strategic element to being specific. If I enter into an argument with someone who’s a climate sceptic and I start by saying, ‘You deny climate change,’ and the other person says, ‘I’m not denying it,’ then I’ve already kind of lost the argument.”

As well as further research, politicians and climate-friendly voters can also take practical actions to counter populist rhetoric, says Lockwood, including ensuring that climate policies are rolled out in a progressive manner that doesn’t play into the hands of the far right.

“One way might be to make sure everyone has access to retraining, higher education. The other is, those people have suffered from stagnant wages, falling wages, actually, in recent years and a squeeze on income. Climate policies can add to energy costs, and so what we need to do is think of other ways of funding climate policies than putting it on consumer bills, which is actually very regressive anyway.”

He points to the Gilet Jaunes protests in France as an example of what can happen when governments don’t take that into account. “The roots of this nationalist authoritarian populist backlash are in people who have been excluded from big social changes in the economy, people who used to work in manual jobs which have now been lost to technical change and globalisation. Their prospects, and their prospects for their children, are not good. They feel they’ve been shut out by the mainstream parties.”

With small numbers and a lack of unity on both policies and party issues, right-wing populists are not yet the threat that they are sometimes made out to be. But this relative powerlessness shouldn’t be counted on as their voices get louder and citizens become increasingly disaffected with mainstream politics.

Updated to include details of the UK‘s Brexit Party.

Main image: Blandine Le Cain/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts