Climate change is arguably the most significant issue facing the world right now. So you’d be forgiven for thinking this is an issue on which it would be easy to hold politicians to account. But you’d be wrong.

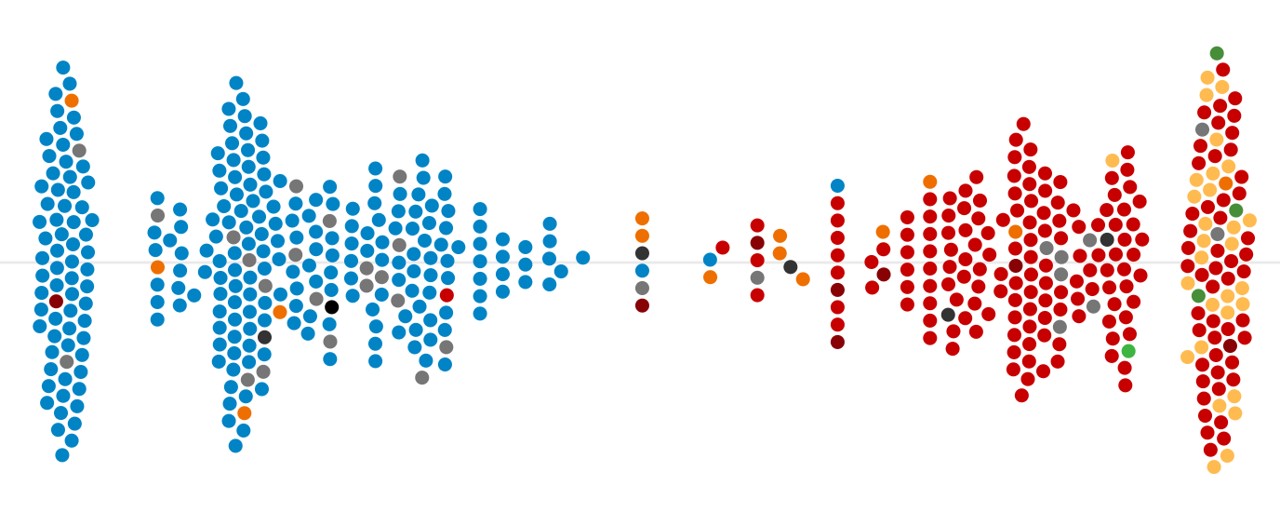

DeSmog collaborated with the Guardian to analyse which of the UK’s MPs have the best and worst records on climate change. We’re very pleased with the Guardian’s climate score league table, and think it offers a fair reflection of where most MPs sit on the issue — today and over the past decade.

With Boris Johnson (who scores terribly, by the way) poised to call a general election as soon as Parliament will let him, and more people than ever caring deeply about climate change, now seemed like the perfect time to do the analysis.

But creating the ranking wasn’t easy.

The UK’s political system is nimble enough to allow serious action on climate change, as the landmark 2008 Climate Change Act showed. But the way laws and policies are made and implemented makes it hard to scrutinise individual MPs’ efforts to take (or block) action.

That’s why we went further than just analysing votes, employing a three-pronged approach to answering what seemed like a fairly straightforward question: which MPs have done the most to drive action on climate change, and which have done the most to obstruct it?

We give all our work to our media partners for free. So if you want to support our work, please become a patron today!

(1) See how they voted

Discussing the project over a cup of coffee, the answer at first seemed obvious: look at how they voted. The data is public, it goes back a long way, it’s easy enough to scrape and analyse — it seemed like a no brainer. But it quickly became apparent this wasn’t as simple as we first thought.

The list was run past lots of experts, and they were all happy we’d got a good spread. And we hope it offers an insight beyond those that can be gleaned from invaluable sources such as TheyWorkForYou and The Public Whip.

Our starting point was the Climate Change Act of 2008. That law put the UK right out front in terms of setting legally-binding climate targets. Seeing who rebelled against it more than 10 years ago remains pretty informative (many of the MPs who did — such as Peter Lilley and Ann Widdecombe — continue to be some of the strongest climate science denial voices in the UK).

But since then, it has become a lot trickier to establish who is a ‘climate leader’ and who is a ‘climate laggard’ through voting alone.

For instance, Parliament recently declared a climate emergency. How? By holding a long debate, at the end of which they looked around to see if anyone objected. No one did. And so a motion was agreed. It was a similar story with the House of Commons’ consideration of the much-vaunted net-zero goal.

You could say that means all MPs agreed. Or it could just be that in this instance not enough people were willing to stick their heads above the parapet to object — and that’s what we’re really trying to get at; not the party line, but how individual MPs — yours and mine and everyone’s — voted on this issue.

The absence of an actual vote means we can’t know for sure, on an MP-by-MP level, who is willing to take bold action on this issue; the kind of bold action that will put the UK back on track to meet its climate targets.

As the Guardian acknowledges:

“The scores are indicative rather than conclusive; the constraints of the party system, the arcane procedures of Parliament and the complexity of the voting process are all factors that are hard to quantify.”

What do we mean by that?

Well, the UK’s political parties (until very recently at least) function on a whipping system — where MPs are (figuratively) beaten into voting with the party line. Under the principle of collective responsibility, if an MP disagrees with the governments position they are also expected to resign their post to vote against it (again, until very recently, at least).

That means that when MPs do break with the party or government line on an issue, it’s a big deal. And it’s why we focused on examples where there were a reasonable number of rebels, and awarded extra points to MPs that voted in that way.

Governments also have a penchant for wrapping up lots of bits of policy in broader pieces of legislation, such as an Energy Bill or the Infrastructure Act. It’s pretty hard to separate out who is voting for what and why in such major votes. So we’ve focused on specific bills and motions to try and mitigate that.

Climate change also isn’t a single issue, it’s a topic that underpins a huge range of sectors and issues. That’s why we were careful to select prominent votes from a range of climate-related topics: from aviation to nuclear power, from renewable energy subsidies to vehicle taxes.

And what did we find? Well, it’s not great news for Boris Johnson’s government.

The average voting score of Johnson’s cabinet was 17 percent, compared with Corbyn’s Labour shadow cabinet score of 90 percent. Jo Swinson and the Lib Dems ended up with middling scores largely because of how they voted during 2010-2015 as part of a coalition government with the Conservatives.

That’s not to say every Conservative MP is anti-climate action or every Labour politician is pro-action; that’s clearly not the case. But the data shows there is a section of the Conservative party that has for more than a decade been doing more to obstruct climate action than anyone else. And some of those MPs, including the Prime Minster himself, are now in government.

(2) Follow the money

It was clear that looking at voting records alone was an insufficient way to measure who is really a leader and a laggard when it comes to climate action, however. That’s why MPs’ interests are also included in the data.

If voting on legislation is only the tip of the iceberg of a parliamentarian’s activity, it makes sense to put on your snorkel and dive below the surface.

Seeing who MPs were taking money from, combined with how they voted, provides a fuller picture of how likely they are to take significant action on climate change. That’s why we came up with a list of around 400 names of individuals and organisations known to push an anti-climate action agenda — many of whom are in DeSmog’s Disinformation Database — to run through the MPs Register of Interests.

Knowing who funds lawmakers is a pillar of democracy. And Boris Johnson’s cabinet again scores pretty badly, which fits with DeSmog’s previous analysis. In the Guardian’s database, there are 10 ministers that received donations or gifts from oil companies, airports, petrostates, climate sceptics or thinktanks identified as spreading information against climate action.

(3) Mapping the network

The list of people and organisations wasn’t based on guesswork. DeSmog has for more than a decade been working hard to identify and track organisations lobbying against climate action.

Lobbying can take many forms, not just giving money — in fact, companies and individuals are being increasingly careful about who they do directly give to, often preferring to use intermediaries such as thinktanks or campaign groups to do their bidding.

Some of the organisations on our list were simply fossil fuel companies (large and small), who have a vested interest in maintaining the high-carbon status quo. Others were known associates of groups based in and around offices at 55 Tufton Street, just around the corner from Westminster.

As DeSmog’s investigations have previously revealed, these groups regularly lobby government ministers to strip back environmental protections as part of a wider project to deregulate markets, often in the name of a hard Brexit. Lots of former Tufton Street staffers have also now found themselves in government, as special advisors to cabinet ministers and number 10.

These groups are very secretive about who funds them and how they operate, and the UK’s lobbying regulations remain weak. Ministers have become adept at hiding the details of their meetings with key figures. And in some cases — such as with All-Party Parliamentary Groups — records of members or participants are patchy or even non-existent (which is why they don’t form part of the analysis).

That’s why organisations such as DeSmog remain necessary — to keep a close watch on political activity that goes beneath the tip of the iceberg, to understand who it is that is lobbying against climate action.

Despite the significant systemic obstacles to assessing this seemingly simple question, we think that with the Guardian and other partners we’ve managed to create a useful tool for voters interested in climate change to consult whenever they may be called to the ballot box. Because, ultimately, that remains the most definitive way to hold power to account on the most pressing issue of today.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts