On December 31, 2019 many of us were reflecting on the past year and thinking about what opportunities lay ahead. Few were paying close attention to early reports of unexplained cases of pneumonia thousands of miles away in Wuhan, the large capital city of China’s Hubei Province.

But less than three months later, on March 23, Boris Johnson was ordering a national lockdown to try and stop that virus, by then known worldwide as COVID-19, from raging across the UK. This came 52 days after the chief medical officer of England had confirmed the nation’s first two cases.

The coronavirus crisis once again saw the UK divided — between those putting their trust in public health experts and their recommendations, and those quick to question the science on which the government claimed to base its decisions for controlling the pandemic. For those who have watched the decades-long efforts to slow climate action, this was a familiar phenomenon. And the coronavirus pandemic seemed to give fresh ammunition to some familiar faces.

A close look at commentary on both COVID-19 and climate change reveals significant crossover between unqualified voices casting doubt on experts recommending action.

Why?

“There’s nothing mysterious about this,” says Stephan Lewandowsky, a professor of cognitive science, who studies the persistence of misinformation in society at the University of Bristol.

“I think COVID is just climate change on steroids in a particle accelerator,” he says. “The same forces are happening: you have the inevitability of a virus which is the same as the inevitability of the physics. And opposing that you have politics which motivates some people to deny the inevitables and instead resort to bizarre claims.”

Find out more about the crossover between COVID and climate science denial in DeSmog’s special series

‘No need to panic’

Commentators with a history of casting doubt on established climate science first turned their attention to COVID in the days just after Chinese authorities ordered the 11 million residents of Wuhan, a city the size of London, into lockdown.

On January 24, Ross Clark, a columnist for The Spectator who has lamented “hysteria” around COVID-19, said there was “no need to panic about coronavirus” despite warnings from leading epidemiologists about the potential spread of the outbreak.

On January 29, British economist Roger Bate similarly argued on the website of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a climate science denying free-market lobby group, that news reports around COVID-19 were unnecessarily sparking a major political reaction.

“A contagion will happen at some point, and it’s important we recognize it and react. Unless the coronavirus mutates into something far more dangerous, this isn’t it,” he wrote.

The idea that governments and the media were overreacting to the coronavirus threat was echoed by libertarian online magazine Spiked, which has taken funding from notorious backers of climate science denial the Koch family, and has included Bate and other AEI scholars among its contributors. It published an article as early as January 30 saying there was “mass hysteria in the newsrooms” around COVID.

By mid-February, the World Health Organization had declared that the threat of COVID-19 spreading across the world was “high” — yet a relaxed attitude continued to prevail among some commentators.

On February 19, centre-right blog ConservativeHome published an article by Daniel Hannan, a columnist and former Tory MEP, claiming that COVID-19 was unlikely to be as lethal as the common flu.

Hannan, a leading figure in the UK’s campaign to leave the EU, has links to various American lobby groups that have spread misinformation on climate change including the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation. He encouraged ConservativeHome readers to “cheer up” and discouraged “panic” over the virus. That message was taken up by Clark in another Spectator article, arguing that “coronavirus hysteria” was “the latest phenomenon to fulfil our weird and growing appetite for doom.”

Clark told DeSmog he stood by his analysis but acknowledged: “Clearly, COVID-19 took off more than I, or virtually anybody imagined it would at that stage.”

“There is a very broad range of opinions among virologists, epidemiologists and others who might be regarded as expert in this field,” he said, “so the idea that I am at odds with some mythical consensus of expert opinion is false.”

“I have been around long enough to know there is no such thing as scientific consensus on either issue [climate change or COVID], nor indeed on any matter where evidence is still emerging and open to wide interpretation,” he added.

Even after the World Health Organization declared the contagion to be a pandemic in early March, commentators who have long cast doubt on warnings issued by climate scientists continued to deny that COVID-19 was a major threat.

Mail on Sunday columnist Peter Hitchens claimed that Britain was infected by a “bad case of madness,” arguing that restrictions were being “driven by hysteria” and “unreason.”

The language was familiar: Hitchens has previously rejected science showing human activity is responsible for global warming, and labeled measures to tackle climate change such as environmental taxes as a “sort of madness.”

For Lewandowsky, this “hysteria” narrative is part of a wider phenomenon of undermining expertise across the board, from Brexit, to climate change, and now COVID-19.

Lewandowsky points out that this also extends to many on the fringes of the political debate, such as controversial commentator Katie Hopkins, who had over a million Twitter followers before the platform banned her, and has said the public were being “played” by the government for being asked to wear face masks. Or Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, who described a police visit to his home as “lunacy” after he apparently broke lockdown rules.

Both have also cast doubt on the reality and seriousness of climate change.

“They’re quite explicit about saying that one person’s fact is another person’s lie, because that then enables them to avoid accountability,” Lewandowsky argues.

Miracle cures and conspiracy theories

These commentators’ contributions to the debate haven’t been without consequence. Some have spread conspiracy theories that have had real-world impact, while others have admitted to ignoring official safety guidelines, putting the public at risk of catching the disease.

Columnist James Delingpole wrote in a March 28 article for the Spectator Australia titled ‘Wu Flu Notes’ that he had gone about his daily business despite having symptoms that align with coronavirus and that it was possible he had “infected lots of graduates.”

Some days later, Delingpole posted a tweet claiming a “high-powered zinc formula” had helped him recover from the illness without the need to go into intensive care – despite little being known about whether any such formula can be a cure for the virus.

He went on to write, “what I’d like more than anything is for this stuff to be available on the open market for everyone. But to mass produce it my friend needs ££££. If I crowdfunded it who’d be interested?” He concluded his request by asking for “potential big money backers.”

I haven’t told you all about how I got through coronavirus despite having several underlying health conditions which, I’m convinced, could have led to intensive care. Essentially, it’s a high powered zinc formula, created by a friend, which disrupts the cytokine storm.

— Professor Dr Sir James Delingpole OM QC (@JamesDelingpole) March 30, 2020

Delingpole’s zinc promotion was comparable to comments made by US conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, who, a few weeks prior, had received a cease-and-desist letter from a top New York attorney based on claims he had marketed and sold fraudulent COVID-19 treatments on his conspiracy website. US President Donald Trump was also widely criticised for suggesting that disinfectant taken internally could be a treatment for the virus.

Theories about miracle cures can take hold partly as a result of personal politics, Lewandowsky argues. Under lockdown, “you’re asked to stay at home and to look after other people by not doing what you’d like to do, and that is very challenging if you’re a believer in personal freedom and autonomy,” he says.

The same can be said of the motivations for spreading misinformation on climate change: “A lot of climate denial is very high-pitched, frenetic, emotional, angry, toxic – and that’s all triggered because people’s identity is at stake.”

The desire to reach for conspiracy theories may also stem from a need to feel that individuals still retain some control, says Evita March, a senior lecturer of psychology at Federation University Australia. “Conspiracy theories offer the believer some comfort in that there is still behavioural predictability,” she says.

And there were plenty of conspiracy theories flying around, pushed by long-time climate science deniers.

Piers Corbyn, brother of former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, was quick to promote the idea that coronavirus was the fault of politically liberal billionaires, and that it was related to the Chinese-developed 5G mobile network.

The latter conspiracy, also promoted by Infowars’ Jones, had significant real-world consequences. Over the Easter weekend it was reported that 20 phone masts had been subject to arson attacks. According to Mobile UK, the trade association for four mobile network operators, an estimated 50 masts had been targeted by April 15.

David Lawrence, a researcher at campaign group Hope Not Hate, told DeSmog that theories around 5G have existed for a number of years, so “the stage was already set.” ”When the global COVID-19 outbreak occurred, there was both a susceptibility to be exploited and a ready-made explanation to hand,” he said.

“In some ways this is similar to climate change,” said Lawrence, “in that people who work in industries that would be negatively affected by efforts to reduce carbon emissions might be more likely to find reasons to reject the scientific consensus.”

Such conspiracy theories become popular — whether in relation to climate change or COVID-19 — because they are a means of “simplifying and attributing blame,” particularly during a time when “people feel that they have lost control over their lives,” says Lewandowsky.

“Some will seek comfort in the idea that there are bad people out there causing the pandemic because, for some, knowing there are bad people responsible for terrible things is more comforting than to assume that these things are uncontrollable,” he says. “It allows people to direct anger at someone.”

Distrusting modellers

Many commentators directed their fire at a familiar foe — scientific models.

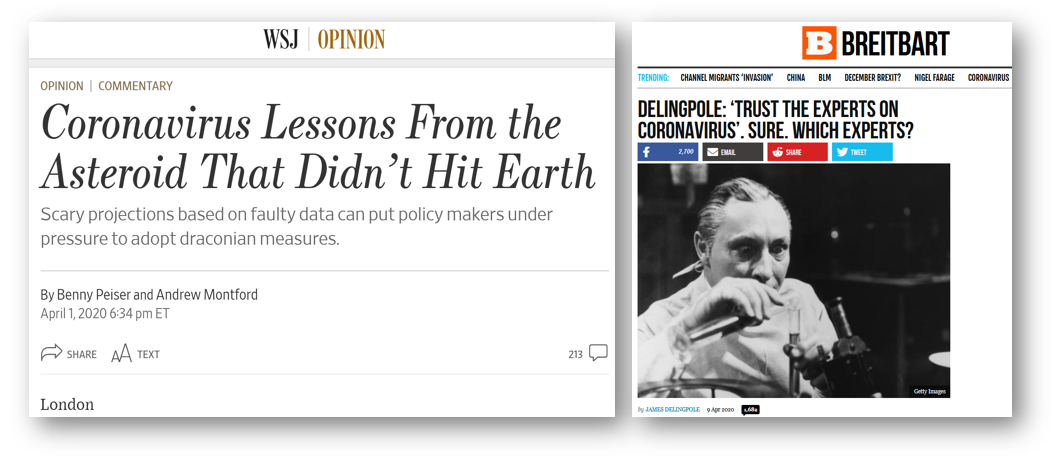

On April 1, the same day the United Nations announced the postponement of the annual UN climate change conference, two prominent UK climate science deniers argued in The Wall Street Journal that the pandemic had “dramatically demonstrated the limits of scientific modelling to predict the future.”

Benny Peiser and Andrew Montford, the Director and Deputy Director of the UK’s principal climate science denial campaign group the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), criticised policymakers for using academic research that was subject to a “lack of quality control.” “In normal times this doesn’t matter much, but it’s different when studies find their way into the policy world,” they wrote.

They did not mention that the GWPF’s own approach to ‘peer-review’, which undercover reporters in 2015 showed operated on the basis of sending reports to its members of its own advisory council. The model has been described by UK charity Sense About Science, whose Advisory Council included GWPF advisor Matt Ridley, as “a way of trying to give scientific credibility to certain claims in the hope that a non-scientific audience will not know the difference.”

Eight days later, Breitbart’s Delingpole similarly criticised scientific modelling, dismissing research from the University of Washington forecasting more than 150,000 deaths from the disease across the US as “operating in the realms of purest fantasy.” Whether on climate change or the pandemic, “we have no idea whether or not we can trust” scientific experts and their modelling, Delingpole argued.

Clark takes a similar view, telling DeSmog: “on both COVID-19 and climate change there are a lot of people who seem to favour the results of modelling over real-world observation.” Those who want action “will latch on to any model” that suits their ends, he claimed, and will “decide that is ‘the science’, that it is fact, beyond all challenge.”

An article in Spiked likewise argued in April that “worst-case scenario thinking” and “doomsday forecasts” from models had clouded political judgement, referencing the obesity crisis, swine flu, and climate change.

This process of regularly casting doubt on models represents the “weaponisation of the scientific method,” says Imran Ahmed, founder of the Centre for Countering Digital Hate. “Those sorts of sly tactics that have been used by these groups have amounted to an entire culture of how they spread information, spread ideas, and build audiences for their groups.”

“It’s expressed through philosophical strands which are anti-expert, faux-populist and conspiracies” and can include the “incel movement, climate denial, vaccine denial, identity-based hate,” he argues.

“As new facts emerge and as the understanding of the scientific movement changes,” says Ahmed, “these actors look back at previous consensuses and say, ‘see, they were lying back then.’”

Attacking environmentalists

As well as attacking coronavirus experts on their response recommendations, many commentators who oppose climate action also attacked those looking further ahead by putting forward proposals to ensure recovery plans were consistent with governments’ environmental pledges.

For months, commentators who regularly question the veracity of mainstream climate science denounced environmental activists for supposedly distracting the world with climate change amid the threat of pandemics.

On March 12, Telegraph columnist Sherelle Jacobs argued that university funding should be redirected away from climate change research and towards “the scientifically uncontested problem of pandemics.” The day after, when the UK was effectively put under a national lockdown, Dutch climate science denial group CLINTEL published an open letter titled “Fight virus not carbon.”

Greenpeace, The Climate Group, and many other environmental organisations believe that the government should include environmental policies in coronavirus economic recovery measures to “build back better,” particularly as the country seeks to position itself as a climate leader ahead of hosting the UN climate talks in November 2021.

Some commentators spun this argument to imply that the environmental movement was happy that the virus has spread.

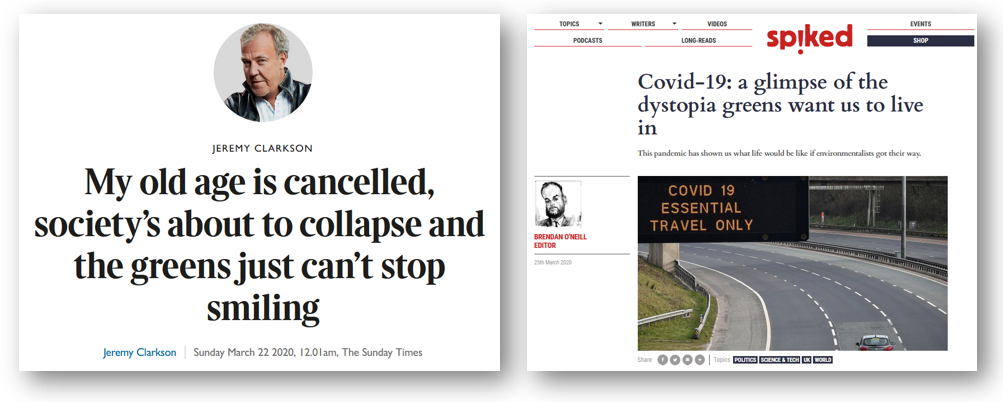

On March 22, former Top Gear presenter Jeremy Clarkson claimed in the Sunday Times that “greens just can’t stop smiling” because COVID-19 was “their idea of a wet dream.” Spiked contributor Ross Clark echoed this position in a response to DeSmog’s questions, saying that “there is a strand of opinion on the left which wants these crises — climate change and COVID — to be as big as possible because they see it as a way of undermining capitalism, and other aspects of our lives, and reforming society in their own dream vision.”

On March 25, a couple of days after Clarkson’s polemic appeared, Spiked editor Brendan O’Neill similarly argued that the pandemic was “a glimpse of the dystopia greens want us to live in.”

“The truth is that if the COVID-19 crisis has shown us anything, it is how awful it would be to live in the kind of world greens dream about. Right now, courtesy of a horrible new virus, our societies look not dissimilar to the kind of societies Greta Thunberg, Extinction Rebellion, green parties and others have long been agitating for,” he wrote.

O’Neill reiterated this position when contacted by DeSmog, saying both the “green movement” and the reaction to COVID represented “privileged Westerners taking political decisions and actions” to the detriment of some of society’s most vulnerable. “Progressives should be questioning the impact of the reaction to COVID-19 on working people and poor people,” he said.

In June, 57 charities wrote to Prime Minister Boris Johnson asking him to put the creation of jobs in low-carbon sectors at the forefront of his economic recovery plans. They also asked the government to cancel the debts of developing countries struggling with both the impacts of the pandemic and the climate crisis.

Delingpole later wrote in a column for Breitbart saying environmentalists were celebrating the lockdown as a blueprint for a “new world order.” The GWPF took this argument one step further, publishing an image of a crying woman with the text, “net zero, like lockdown but permanent” — a reference to the UK government’s plans to slash the country’s emissions.

As these pieces were appearing, a Twitter account claiming to represent the climate protest group Extinction Rebellion (XR) in the East Midlands posted an image of an XR-branded sticker on a lamppost with the words, “corona is the cure, humans are the disease.”

Official XR accounts were quick to condemn the tweet and said that they were not affiliated with the newly created account, which has since been deleted. But various outlets and commentators used the tweet to condemn the protest group.

Gaia Fawkes, the environmental section of political blog Guido Fawkes, suggested the post showed that XR was “in favour of extinction,” though it acknowledged coordinators of the organisation had “distanced themselves” from the supposed splinter group. A spokesperson for the site told DeSmog it stood by its reporting despite well-publicised doubts over the authenticity of the East Midlands organisation, stating it was “unaware of any publicly available list of ‘official’ [XR] groups at the time.”

The GWPF likewise claimed the Twitter account’s “anti-human sentiment” was “widely shared” among environmentalists, rejecting claims that the East Midlands account was fake.

Like what you’re reading? Support DeSmog by becoming a patron today!

Author and Guardian columnist George Monbiot suggests that while it is predominantly money that is behind climate science denial or tobacco industry lobbying, “with COVID-19, the motive definitely varies,” but the outcome is essentially the same.

“There are a lot of very well-paid people who are very professional and they’re using the expertise that they’ve gathered in other areas of dispute about scientific facts and the policies arising from them, and applying those directly to the pandemic,” he argues.

“Take their power seriously, but don’t take any of their arguments at face value,” Monbiot concludes. “It’s not worth trying to deconstruct the nonsense they come out with.”

Political impact

Unlike in the EU referendum or Trump’s presidential campaign, pushing anti-expert rhetoric may no longer be a winning strategy in the wake of COVID-19. Polling shows that despite worry about the pandemic and its impacts, the public still wants governments to tackle climate change. And politicians attaching themselves to the anti-science bandwagon are now struggling in the polls.

For the Centre for Countering Digital Hate’s Imran Ahmed, attacking the concept of expertise around COVID-19 is “the first truly great strategic mistake by those who espouse this radical world view.”

The US and UK are two of the countries hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic, and both have leaders “who have been denying evidence and fact,” says Lewandowsky. “Johnson and Trump are creating a situation in which the very thought that we could establish a common truth is under attack,” he says. Both are regularly backed by commentators who also openly question the concept of expertise, whether on climate change or coronavirus.

But these positions have begun to hurt both leaders. Johnson has plummeted from a position of public popularity prior to the UK’s lockdown to a negative approval rating almost four months later. And the gap between the majority of Americans who disapprove of Trump’s leadership and those keeping faith with the president now sits at around 15 percent, numbers that could see him lose November’s election.

That may reflect a wider shift in the public mindset, Lewandowsky argues: “My hope is that the COVID crisis has kind of given us a reset here, and there’s some evidence that people are beginning to say that we do need experts and data.”

Main image © Andy Carter. Editing by Emily Gertz and Mat Hope.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts